Flightdeck Friday: Flight of the Truculent Turtle

Fifty-five hours and 18minutes. 11,236.6 nautical miles. No GPS, no inertial nav, no fly-by-wire, no computers save the biologic ones and the whizwheels. No movies, no SATCOM, no sleeper seats. No in-flight refueling – no stops. No digital weather radar. Four aircrew, one nine-month old baby ‘roo and 8,592 gallons of AVGAS.

Non-stop, Austalia to the United States.

This was the flight of the Truculent Turtle that began 29 Sep 1946 and set a record that would endure until Burt Rutan broke it in 1987 with his ’round-the-world flight.

During the recently completed war, the Navy had opportunity to use a variety of land-based long range bombers as patrol aircraft. Ranging from the PBJ Mitchell to the PB-1 Flying Fortress and the PB4Y series Liberator the Navy had an opportunity to compare and contrast advantages and shortfalls, and in the process, determined it needed its own design. Hence the birth of the P2V Neptune (in a nutshell).

With the end of the war and accompanying major cuts in production lines occurring just as the P2V was coming into production, Navy leadership felt something major was called for to demonstrate the capabilities of this new aircraft. With a flare for the dramatic (and less risk adverse, it seems than today’s leadership) then-CNO Nimitz proposed a non-stop flight from Perth, Australia to Washington DC for the purpose of evaluating the physical capabilities of the aircraft and the impact of long, open water flights on the physiology of the aircrew.

Of course, the fact that the pursuit of various records as a way of showcasing the latest/greatest aircraft was an unwritten rule of the day played no small role. Egging the competitive juices was the fact that the current record was held by a B-29 that had flown non-stop from Guam to Washington DC the year previous – a little over 7500 nm; along with rumors the Army Air Force was planning a more ambitious flight across the North Pole from Hawaii to Cairo, Egypt – a trip of some 9,000+ nm.

To make the flight, the first production model P2V-1, BuNo 89082 was pulled off the line and converted to make the flight. Weight was obviously a driving factor and anything that would not contribute to extending the range had to go. Off came turrets, guns and armor. Additionally, oxygen equipment and cabin heaters as well as radio equipment in the aft fuselage. In their pace went tanks for holding gas – lots of gas. As finally configured, this P2V consisted of:

– 2,200 gallon tank in the bomb bay

– 1,542 gallons in the outer wing tanks

– tip tanks holding 40 gallons apiece

– nose tank with 858 gallons

– rear fuselage tank with 2,028 gallons

– sonobuoy tank with 128 gallons

and counting the 140 or so gallons of avgas in the lines between the tanks, a total of 8,592 gallons – 5,000 more than normal P2V. (note: in the event of an emergency there was a rudimentary fuel dump installed that could dump up to 5200 gallons in about 6 minutes).

Pearce aerodrome was selected given its 6,000 ft runway and JATO bottles would be used to boost the overloaded aircraft into flight. A crew of four, smaller than the normal complement would make the flight: CDR Thomas D. Davies would be the pilot in command, CDR E. P. Rankin his copilot, with CDR W. S. Reid and LCDR R. A. Tabeling acting as relief pilots as well as handling navigation and the radios.(ed. and not a single JO amongst them… – SJS).

The weather deities pointed towards the 29th of Sept as the favored date and at the appointed time, the Truculent Turtle (so-named for the project, Operation Turtle, that developed these mods) was wheeled out to the end of the runway, JATO packs attached and one final fueling. Already 13 tons over its regular max weight, the Truculent Turtle took the active and made final preps for launch. As (then) CDR Rankin describes it:

Late afternoon on the 29th the weather in southwestern Australia was beautiful. At 1800, the two 2,300-hp Wright R-3350-8 engines were warming up. We were about to commence a takeoff from a 6,000-foot runway at a gross weight of 85,561 pounds (the standard P2V-1 was rated at 61,000 pounds), of which about 50,000 pounds were gasoline. Sitting in the copilot’s seat, I remember thinking about my wife, Virginia, and my three daughters and asking myself, “What am I doing here in this situation?” I took a deep breath and wished for the best, knowing the takeoff would be the greatest risk of the entire flight.

The tower had cleared us for takeoff with a cheery “Good luck.” I pushed the throttles forward to 2,800 rpm. The Turtle reluctantly began to roll and gradually picked up speed. When we reached 75 knots at about 3,000 feet down the runway, the lumbering smoothed out as weight began to shift from wheels to wing lift. At 87 knots, Davies fired the four JATO (jet-assisted takeoff) bottles that increased our thrust by 25 percent for about 10 seconds. At 4,500 feet, the Turtle passed through 115 knots and was very light on the wheels. Tom said, “She is supposed The aircraft passed by 4,728 feet as the wheels began to fold-the props were five feet above the runway. With the wheels housed at runway marker 5,500 feet, the Turtle was now responding efficiently to flight controls and commenced a gradual climb. At 150 knots, she behaved beautifully in a shallow left turn to fly over Perth at 5,000 feet.

We were airborne and on our way.

Over or by New Guinea, Bougainville, Midway and Oahu – all names pregnant with memories from a few short years ago in the Pacific. Because of the shorter-ranged radios they were left with, they were out of radio contact for more than 18 hours in the the middle stage of the flight. They had received an update that Seattle, landfall in CONUS, was experiencing moderately bad weather and so route of flight was adjusted to go feet-dry in Northern California instead.

And the challenges wouldn’t end there. The weather in the western US was the pits – strong headwinds, icing (they picked up an estimated 1000 pounds of ice around Ogden, Utah). Having been given wide latitude to land at a destination of their choosing, because of concerns over fuel remaining, CDR Davies opted for a stop at Columus’ Naval Air Station. From there they would continue on to Anacostia NAS in Washington, DC,

That night over the Rocky Mountains, weather became a major factor. Freezing rain, snow and ice froze on the wings and fuselage, forcing us to increase power to 80 percent to barely stay airborne. During the Turtle’s modification, the anti-icing and de-icing equipment had been removed to decrease weight. The turbulence and heavy fuel use for almost three hours to maintain flying speed at 13,000 feet cut 500 miles of distance from our flight.

The record set by the Turtle would stand until January 1962 when an Air Force B-52 traveled 12,519 nonstop miles from Okinawa, Japan, to Madrid, Spain. And the Dreamboat made her trip a couple of days after Truculent Turtle – but it fell short in miles traveled.

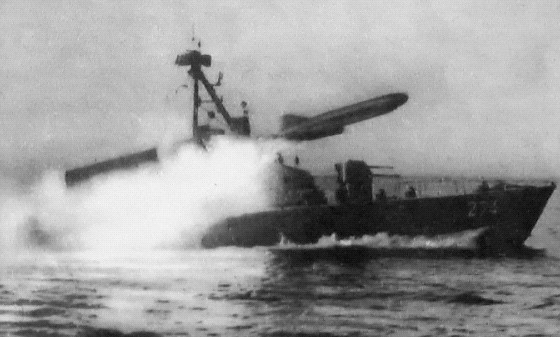

(Photo taken not long after landing at NAS Columbus, OH – note the 9-month old kangaroo lying down – one of the very few photos with the ‘roo)

General characteristics

- Crew: 7-9

- Length: 91 ft 8 in (27.9 m)

- Wingspan: 101 ft 4 in (30.9 m)

- Height: 29 ft 4 in (8.9 m)

- Wing area: 1,000 ft² (93 m²)

- Empty weight: 49,548 lb (22,475 kg)

- Loaded weight: 73,139 lb (33,175 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 79,895 lb (36,240 kg)

- Powerplant:

- 2× Wright R-3350-32W Cyclone Turbo-compound radial engines, 3,700 hp (2,800 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 403 mph (649 km/h)

- Range:

- Combat: 2,200 mi (3,500 km)

- Ferry: 4,350 mi (7,000 km)

- Service ceiling 22,000 ft (6,700 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,760 ft/min (9 m/s)

- Wing loading: 73 lb/ft² (360 kg/m²)

Armament

- Rockets: 2.75″ FFAR in removable wing-mounted pods

- Bombs: 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) including free-fall bombs, depth charges, and torpedoes

Sources:

I saw the Turtle every day at NAS Moffett Field in the mid ’80s, when it was on static display outside the Operations building. There was an information display about the plane and its accomplishments, but this account really tells the tale. Thanks!