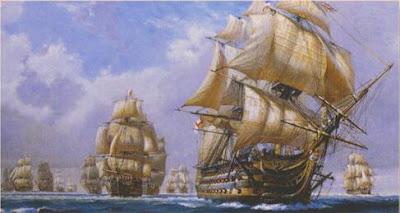

R.I.P. for the Royal Navy?

THE STRANGE DEATH OF THE ROYAL NAVY

By ARTHUR HERMANJanuary 14, 2007 — A 400-YEAR epoch of world history is about to draw to a close. If Britain’s current Labor government has its way, Britain’s Royal Navy will mothball at least 13, and perhaps as many as 19, of its remaining 44 ships, or nearly half its effective fleet.

With one bureaucratic stroke, the Ministry of Defense will end a naval tradition reaching back to Sir Francis Drake – reducing the Royal Navy, which 40 years ago was still the second-largest fleet in the world, to the size of navies of countries like Indonesia and Turkey.

This decision, of course, has to be set against the background of Britain’s decades-long decline as a world power. But it also reflects a struggle for the soul of Great Britain that has been going since World War II: Is Britain part of an English-speak ing, Atlantic-based strategic alliance that includes the United States and Canada? Or is it part of Europe as envisioned by technocrats in Paris, Brussels and Berlin?

NEXT month’s final decision on whether to scrap the Royal Navy may supply us with the answer. Because the Blair government’s drastic plans include more than taking existing ships out of commission. The service’s entire future as a blue-water navy (that is, a navy capable of operations outside Britain’s own waters) may be forfeit. According to The Daily Telegraph, plans for two new fleet carriers of the kind vital for fighting today’s War on Terror and projecting power overseas – and for which $6.9 billion had already been set aside – will also be scrapped. Two new destroyers, which were supposed to replace at least some of the retired ships, are also out of the picture. The Telegraph even reports (Jan. 8) that all officer promotions in the navy are to be suspended for the next five years.

Many in the government and in the media blame these cuts on Tony Blair’s support for the U.S. war in Iraq. They claim the British troop presence there is eating up the British defense budget, leaving the other services like the navy to fight over table scraps.

But this is far from the whole story. Since the mid ’80s, British defense spending has shrunk by more than 30 percent, to less than 2.5 percent of GDP. Today it is at its lowest level since 1930. Even welfare states such as France and Germany spend more on their military. (Meanwhile, Blair is busy hacking back the British commitment in Iraq from 7,000 to 4,500 troops – less than 4 percent of the coalition total.

The truth is that for two centuries Britain and the Royal Navy played the role of globocop, policing the world’s sea trade lanes which keep the global economy going. (Even today, 95 percent of the weight of all intercontinental trade travels by sea.)

AFTER World War II, the U.S. Navy gradually took over that thankless but essential task; the British felt free to relax. From a postwar peak of 388 ships and submarines in 1950, the Royal Navy had dwindled to 112 vessels in 1980. By 2004 it was

down to just 46.Yet the British navy still takes pride in sharing the globocop burden with the United States in vital strategic areas like the Persian Gulf, and even being able to project power trans-oceanically alone when it has to, as during the Falklands War. Analysts agree that once these forecast cuts go through, this will be impossible. Indeed, a Royal Navy of only 25 vessels would require at least some cooperation from its European neighbors even to defend Britain.

This is an ominous trend for many reasons. It not only increases the burden on the U.S. Navy around the globe. It also reflects a decision to move Britain away from its traditional maritime culture, which is the basis of its strategic relationship with the United States, and toward a decaying Europe.

SINCE 1945, Britain has been torn between the two, like a would-be bride torn between two suitors. Winston Churchill (who was half-American) and Margaret Thatcher knew which to choose. “There is no hope for civilization,” Churchill used to say, “if we drift apart,” meaning the United States and England. Blair, it is true, has been supportive on Iraq. But (like many recent British politicians) he has been eager to ingratiate himself with his continental neighbors, including by compromising Britain’s defense capability. For example, his government stuck with the ill-fated EFA-2000 Eurofighter project, even though it cost Britain 21/2 times the original estimated cost ($37 billion versus $13.7 billion) and the RAF only got its planes after a 41/2-year delay.

Then in 1998 he endorsed Germany and France’s idea of a European Defense Force separate from NATO – and the United States. Again, the cost of cooperation will be to reduce the British army to just one more unit in a European military coalition led from Brussels, not London.

Now come the naval cuts. Pure coincidence? It is not difficult to see the distant hand of the Paris-Brussels-Berlin axis at work. And disasters like this will continue as long as British politicians fool themselves into thinking their future lies with the shrinking economies and aging populations of the continent of Europe.

IRONICALLY, Britain just celebrated the 200th anniversary of its naval victory over France at Trafalgar, which allowed Britain to build an empire and dominate the world’s oceans. If these navy cuts go into effect, France will have a larger fleet than Britain for the first time since the mid-1600s. The victory the French couldn’t win at sea, they will win effortlessly and painlessly at the bureaucrat’s desk.

Arthur Herman is the author of “To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World,” which was nominated for the Mountbatten Prize for best book in naval history in 2005. His latest book, a study of Gandhi and Churchill, will be published next year.