Flightdeck Friday – The F7U Cutlass

Star-crossed (adj.) Opposed by fate; ill-fated.

Star-crossed (adj.) Opposed by fate; ill-fated.

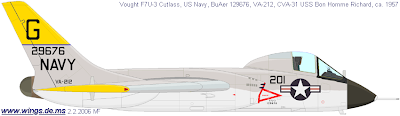

“Star-crossed“ an apt descriptor for this week’s subject – the F7U Cutlass, also known by such endearing labels as “Gutless Cutlass and “Ensign Eliminator. How bad was it? Try this – shortly after the Cutlass arrived at Pax River in 1949 for flight evals, it was taken up for a formation flight/photo shoot – and had a midair with the photo plane, causing both to crash with the loss of their crew. At the cusp of a stall, it had an un-nerving tendency to flip end over end, like a badly designed paper airplane, before entering a spin. Carrier suitability testing was nothing short of a disaster – pilot visibility was unsatisfactory in final carrier approach, wave-off characteristics for latter stage wave-offs were unsatisfactory and the arresting hook assembly was so complicated that its practicability for service use was doubtful. The Blue Angels reached the point with their two demo birds that when they diverted to NAS Memphis with maintenance problems, they left them there, never to fly with the Blues again.

“Star-crossed“ an apt descriptor for this week’s subject – the F7U Cutlass, also known by such endearing labels as “Gutless Cutlass and “Ensign Eliminator. How bad was it? Try this – shortly after the Cutlass arrived at Pax River in 1949 for flight evals, it was taken up for a formation flight/photo shoot – and had a midair with the photo plane, causing both to crash with the loss of their crew. At the cusp of a stall, it had an un-nerving tendency to flip end over end, like a badly designed paper airplane, before entering a spin. Carrier suitability testing was nothing short of a disaster – pilot visibility was unsatisfactory in final carrier approach, wave-off characteristics for latter stage wave-offs were unsatisfactory and the arresting hook assembly was so complicated that its practicability for service use was doubtful. The Blue Angels reached the point with their two demo birds that when they diverted to NAS Memphis with maintenance problems, they left them there, never to fly with the Blues again. Obviously the Cutlass wasn’t designed to intentionally fail – what happened?

Obviously the Cutlass wasn’t designed to intentionally fail – what happened?

least a workable effort towards solving the issue of compressibility effects in control of high speed aircraft by using swept wings. Other documents showed interest and initial work towards a radical, tailless aircraft. Clearly interested, Vought took these design elements and added hydraulically boosted controls and planned to add a new Westinghouse, afterburning engine to create a fast, agile fighter. Instead it turned out to be a bridge too far. The engines, Westinghouse J-34’s at first for the XF7U-1 an F7U-1, were dreadfully underpowered and the J-46’s that mandated a major re-design of the aircraft, yielding the F7U-3 were a story unto themselves in their underwhelming performance and how they hobbled an entire generation of naval aircraft designed around their use. The flight hydraulic system, as a first generation design, was another creature of ill-repute. Consider this story, relayed by (then) LT Whitey Feighner who ended up with a fair amount of cockpit time in the Cutlass, both as test pilot and as one of the two Blue Angels solo pilots flying the F7U-1:

least a workable effort towards solving the issue of compressibility effects in control of high speed aircraft by using swept wings. Other documents showed interest and initial work towards a radical, tailless aircraft. Clearly interested, Vought took these design elements and added hydraulically boosted controls and planned to add a new Westinghouse, afterburning engine to create a fast, agile fighter. Instead it turned out to be a bridge too far. The engines, Westinghouse J-34’s at first for the XF7U-1 an F7U-1, were dreadfully underpowered and the J-46’s that mandated a major re-design of the aircraft, yielding the F7U-3 were a story unto themselves in their underwhelming performance and how they hobbled an entire generation of naval aircraft designed around their use. The flight hydraulic system, as a first generation design, was another creature of ill-repute. Consider this story, relayed by (then) LT Whitey Feighner who ended up with a fair amount of cockpit time in the Cutlass, both as test pilot and as one of the two Blue Angels solo pilots flying the F7U-1:

The company [Chance Vought] pilots had been flying it up to this point, and a few senior Navy pilots had made brief hops in it. The pilot who flew it just before I took it on was D.C. ‘Whisk’ Caldwell. The F7U-1 had one of the first hydraulic flight-control systems. To build feel into it, they had built a heart-shaped cam with a roller on it on the bottom of the control stick. Caldwell took off in the plane one day, and the throw on the stick somehow sent the roller over the edge of one of the lobes on the heart-

shaped cam. Caldwell was immediately faced with a partial

control reversal. When he pulled back on the stick, the airplane went down, and when he pushed forward on it, the airplane climbed. Lateral control was normal. So, he flew around for a few minutes while the base crash crew scrambled and debated whether he should eject or not. He thought, ‘I think I’ll take a little time and see if I can fly this. I think I can land the airplane.’ Sure enough, he landed successfully and rolled in. He got out of the airplane, walked straight into the hangar, sat down at his desk without even taking off his helmet and wrote his resignation from the Navy and quit right there! That’s when I inherited the project.

And this:

…[O]n almost every flight, we lost the hydraulic boost and ended up flying on the mechanical backup system. It took 11 seconds to engage the mechanical system, and you can’t imagine how long that seemed. We had constant hydraulic problems. I probably had 370 hours in the F7U-1 and I can’t ever remember once writing ‘OK’ for the hydraulics on the yellow post-flight evaluation sheet. Something was always wrong. The Vought engineers practically rebuilt the Dash-One. They were wizards at coming up with fixes, but the Cutlass sure taxed them.

Not all was doom and gloom. In the hands of a careful, skilled pilot, like Whitey or the late Wally Schirra, the Cutlass could perform masterfully. Schirra has said that no other aircraft could turn or match his roll-rate in an F7U-3 at altitude. With a pressurized cockpit, that altitude could be as high as 50,000 ft and as a weapons delivery platform, it was relatively stable in delivery mode. Unfortunately its range was horrendous – with a combat radius of around 150 nm it just wasn’t going to go very far with conventional ordnance, much less with the big and heavy first generation tactical nukes. In Vought tradition, it was a good gun platform, with the singular exception of the location of the muzzles under the cockpit created a good bit of flash which took the Cutlass out of the night fight. Around the ship, the Jekyll-Hyde nature continued. With fistfuls of drag, the Cutlass was relatively stable around the pattern with high levels of power utilized to control altitude. Unfortunately, the early models had atrocious over-the-nose visibility, which raised adrenaline levels with the “cut signal from the LSOs:

“When we went to the [USS] Midway (CV-41), an old straight-deck carrier, to do the first carrier landings, we discovered that the problem was worse than we had thought. On the first landing, when I got in close, I didn’t realize that I was skidding the airplane to keep the LSO in sight. He was almost abeam of me when he gave me the cut signal. When I took the cut and looked forward over the nose, I couldn’t see any part of that carrier-nothing, not even the stacks- just water. I knew I had been cut late and I did what I had schooled myself never to do: I dipped the nose because

I thought, I’m really going up the deck! I’ll miss the barricade and go into the pack [of parked airplanes] up front!’ Well, instead, I snagged the number-one wire. The minute I dipped that nose, the airplane fell straight down. I barely made the flight deck! The tail hit eight feet from the ramp and scared the LSO to death…We continued on with the trials, making landings 15 feet off centerline, left and right. On the last landing, the LSO was so nervous that when he gave me the cut, my landing gear was 33 feet above the flight deck! We had pictures to prove it. Not being able to see the deck, I just let it drop from there. I waited and waited to touch down, and just as I started to worry, blam, the airplane hit the deck, and it sounded as though

somebody had taken a big flat board and clobbered the wings with it. The fuselage broke behind the cockpit and you could see daylight at the midpoint, but it didn’t collapse on the deck and break off completely. That ended the project, but we still hadn’t reached the yield on the nosewheel!

Along with the re-design to accommodate the engines, the cockpit was redesigned as well to afford better visibility over the nose. Still, there remained enough problems with the aircraft that the navy eventually brought the program to a halt and by 30 Nov 1957, the last Cutlass departed from squadron service. Over the course of its brief life, the Cutlass claimed 4 test pilot’s and 21 fleet aviator’s lives and while deployed with several squadrons, never saw any combat. Yet what Vought learned in the process helped form the quintessential single-seat gunfighter, the F8U Crusader.

Specifications:

First flight: August 1948

Wingspan: 39 feet 8 inches

Length: 43 feet 1 inch

Height: 14 feet 4 inches

Weight:

Empty: 18,500 lbs

Combat: 24,068 lbs

Range: About 575 nautical miles

Armament: Four pylons, 2000 lbs, four 20 mm cannon

Engine: 2 Westinghouse 4,000 lbs J46-WE-8 engines (Originally J34 engines)

Crew: 1

Sources:

- Tegler, Jan, “Cursed Cutlass: The USN’s Ensign Eliminator. Flight Magazine, October,2003.(http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3897/is_200310/ai_n9342016/pg_1)

- Swanborough, Gordon and Bowers, Peter M. United States Navy Aircraft since 1911. Naval Institute Press, 1990.

- http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/f7u.htm

- http://www.voughtaircraft.com/heritage/

One Comment

Comments are closed.