The Solomons Campaign: Ground Action – The New Georgia Campaign, June 20-November 3, 1943

The next offering comes via CINCLAX – and is a truly detailed review of the ground action in New Georgia as we begin to move – slowly, hesitantly and with great inefficiency (at first) from the precarious foothold established at Guadalcanal. The Japanese will come to learn, as did the Germans on the other side of the world, that once the Americans establish a beachhead, there was no going back – they would relentlessly press their advantage.

And so – the New Georgia Campaign…

– SJS

The Right Place to Go but the Wrong Way to Get There

Solomon Islands

In 1950 Samuel Eliot Morison concluded his final evaluation of the New Georgia Campaign:

The strategy and tactics of the New Georgia campaign were among the least successful of any Allied campaign in the Pacific.

As most of the American planners and commanders were still alive at this time, perhaps Morison was being intentionally soft on them, as his writing excoriates the planners at several other points.

Before 1942 hardly anybody had ever heard of New Georgia, and after 1943 few people would ever hear of it again. Nothing important had ever happened there before, and nothing important afterwards. But for an intense five-month period from June through November 1943, the New Georgia Group of islands would see fierce fighting on land, sea and in the air—and some of the worst American strategic and tactical planning of the war.

The needless complexity of the operation was bewilderingly wasteful, and was often poorly led by Army officers at all levels who had little or no foreknowledge of the terrain and whose troops were woefully inexperienced and physically unprepared. These Americans also had the misfortune of facing one of the most wily and resolute Japanese generals of the Pacific War, Minorou Sasaki.

A Frightful Battlefield

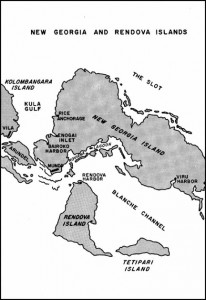

The New Georgia Group in the Central Solomons, on the west side of “The Slot,†is 125 miles long and 40 miles wide. It includes 12 large habitable islands, several dozen small ones, barrier islands, fringing coral reefs and innumerable uncharted coral heads. Like most of the other large Solomon Islands, the New Georgia group is thickly covered by some of the most difficult jungle terrain in the world. So thick is the top canopy that twilight prevails even in broad daylight. The ground beneath is covered with many steep ridges and small rivers—most of which are unseen in aerial photography. Where the terrain flattens near the coastline and the rivers deposit silt carried down from the interior highlands, mangrove swamps usually result.

Just south of the equator, the islands are always hot and rainy, with high daytime temperatures often in excess of 100 degrees. Humidity runs near 100%, and as a result the usual tropical diseases, malaria and dengue fever, proliferate. Constant moisture promotes many debilitating fungal skin conditions, commonly referred to as “jungle rot.†Metal rusts seemingly overnight, and in WW II cloth and leather literally rotted off the soldiers’ equipment. Large insects, land crabs, poisonous snakes, monitor lizards and alligators abound.

In 1943 there were virtually no trails or roads in the interiors of these islands, and when they were eventually cut, the passage of even a company-sized unit turned the footing into a sea of mud. The only large low flat area on New Georgia was the former copra plantation zone around Munda airfield near the south tip of its northwest corner.

Charts were another problem. They were all pre-World War II, and some even went back to German Admiralty charts from the 1890s. Coral reefs, barrier islands and rivers were often missing, and few soundings had ever been taken. All the larger islands were simply labeled “densely wooded” and the few elevations given were only approximate.

Initial Plans

After the February Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal, COMSOPAC VADM William Halsey and his amphibious commander RADM Richmond Kelly Turner, had been planning the next step towards Rabaul. In fact, planning went on for months, both at Pearl Harbor and at Halsey’s HQ at Noumea.

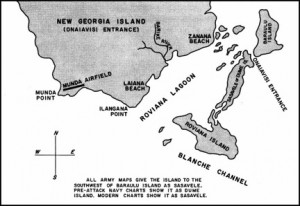

The immediate focus was on four of the largest New Georgia Group islands, especially on New Georgia itself, where in the fall of 1942 the Japanese had built an airfield on the southwest corner at Munda. Periodically they had used this 4700-foot runway as a launching pad for raids on Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, roughly 180 miles to the southeast. It was also used to stage through attacks from Bougainville and Rabaul, so from an American standpoint Munda had to be neutralized, and if possible captured.

Rendova, Kolombangara and Vangunu were also to be targeted. Rendova, because it offered a useful anchorage and was also within artillery range of Munda; Kolombangara, because of its base and airstrip at Vila; Vangunu, because it was thought that Wickham Anchorage could offer a useful base from which to attack New Georgia.

It was an ambitious plan, but Turner & Staff were confident they had the Japanese on the run and would soon have many new tools for their operation. New amphibious ships like the LST, LCI and LCT were finally making their way to Lunga Roads at Guadalcanal and Purvis Bay (on Florida Island, near Tulagi). AIRSOLS now had over 300 planes on Henderson Field (now expanded to four strips), and many of them were new types like the F4-U Corsair and the fast P-38 that had showed their mettle in helping to repel Yamamoto’s April 1943 I-Offensive.

Turner had come to the South Pacific directly from 2+ years as Director of the Navy War Plans Office in Washington, where he had impressed everybody with his intellectual brilliance—and alienated many more with his prickly, know-it-all personality. He had no previous amphibious or ground combat experience, so Watchtower was on-the-job training for him. Still, he had gained immeasurable experience in amphibious landings and jungle warfare during the 6-months successful Guadalcanal campaign. Or so everybody thought in the spring-summer of 1943.

Offense vs. Defense in the Jungle

What nobody seemed to realize was that jungle fighting had two different components: defensive and offensive. For five months Turner and his Marines (Vandegrift, 1st Marine Division) had waged an almost exclusively defensive war on Guadalcanal, repelling repeated Japanese attacks and handing them heavy losses. Turner was fortunate to have landed and established an increasingly strong defensive perimeter without any significant opposition. When the Japanese attempted flanking attacks, they usually had to slog their way through heavy jungle, and invariably their exhausted troops were forced to abandon much of their equipment along the way. They always arrived at their jump-off points days behind schedule, making coordinated attacks almost impossible. The saga of Gen. Maruyama’s trail cutting around Mt. Austen is a good example of these problems (see John Toland’s Pulitzer Prize winning Rising Sun).

The Marines, and later the Army’s Americal Division, had spent 90% of their time defending the Henderson perimeter, so in effect they had a much easier time of it. When they went on the attack, first on the Matanikau for example, things turned out badly as the offensive-defensive roles were reversed. They soon found that it was one thing to defend in deep jungle but quite another to attack.

It was not until December, when the Japanese 17th Army was largely starving and exhausted, that the Americans began to have offensive success in their push north along the coastal plain towards Cape Esperance. In hopes of diverting this move, the Japanese took about 600 men and built several strong points on the slopes of Mt. Austen; the American commander, now Army Gen. Alexander Patch, took the bait. Reducing places like “The Gifu,†“The Galloping Horse†and “The Sea Horse†took several regiments weeks and several hundred KIAs. The Japanese had become skillful jungle defensive fighters, especially in building interlocking fields of fire for their multiple pillboxes and takotsubo (literally “octopus trapâ€) fighting holes, many so cleverly camouflaged that they could not be seen until one was almost on top of them. The standard Japanese cartridge for rifles and light machine guns was the 6.5 mm Arisaka. Compared to the standard U.S. .30 caliber round (.30-06), the 6.5 made a small report and very little muzzle flash, so their positions were not as easily revealed. The Japanese were also very proficient night time infiltrators, terrorizing many an inexperienced soldier with stealthy attacks, deceptive yells, insults and the like. The experienced and better-trained Marines had proper fire discipline; unfortunately the green Army soldiers usually did not.

With all this in mind, it would have been sensible for Turner to have taken note and also investigated some of the similar jungle problems the Army had faced earlier in New Guinea, especially in the painful Buna-Gona operation. For sure, any further Solomons operations would face these same problems.

Somewhat complicating the American plans was that Turner was scheduled to depart the theatre in mid-summer in order to begin planning for the Gilberts invasion (Galvanic) tentatively scheduled for November. His replacement, RADM Theodore “Ping†Wilkinson, had been on Halsey’s staff in Noumea as Deputy Commander SOPAC. An able man, and as affable as Turner was not, he would be handed the ball at a most inopportune time. It was especially awkward, as Turner was late in joining the operation; he’d been sick with malaria and dengue fever and stayed for about 10 days in June aboard a hospital ship in Noumea. With this in mind, it might have been an opportune time for Wilkinson to take over, but neither Halsey nor Turner made the move. Eventually change of command was effected on July 15th, just when the New Georgia operation, codenamed “Toenails,†was bogging down.

American & Japanese Strategy and Plans

In early 1942 the Japanese had bypassed the New Georgia Group in their southward move towards Guadalcanal, Tulagi, the New Hebrides and New Caledonia—until the Guadalcanal battle hung in the balance in fall 1942. Then they landed at Munda Point, New Georgia, on November 14th, and beginning a week later, built a 4,700-foot crushed coral airstrip during the next month. Following this, a Japanese airfield was also built at Vila on Kolombangara Island, a scant 22 miles to the northwest of Munda. Two Special Naval Landing Forces (SNLF) units were provided, and the Japanese rapidly built up defenses around these two very usable and mutually- supporting airfields. After their initial camouflage ruses were uncovered, the Americans repeatedly bombed these strips, however the Japanese quickly filled in the craters and had them up and running the following morning. On the American side, there were now four airstrips at Henderson plus two new ones in the Russell Islands (captured February 1943, some 60 miles north of Henderson). During June alone, AIRSOLS planes made 1455 sorties against Munda, while cruisers and destroyers made several bombardments.

Further north up the Solomons, the Japanese also expanded their landing barge facilities near Horianu on Vella Lavella Island, about sixty miles northwest of Munda. By the late spring of 1943, the Japanese had roughly 10,500 defenders in the New Georgia Group, about 3000 at Munda, 6000 on neigboring Kolombangara and the balance distributed around other islands—including Vella Lavella.

Initially the Japanese could not be completely sure the next American move would be to New Georgia, but after the seizure of the Russell Islands they could be reasonably confident that Munda would be the next target. The Japanese commander, Maj. Gen Minorou Sasaki, reckoned that the Americans were most likely to attempt to land at Bairoko, a small harbor about 7 miles north of Munda. A direct assault on Munda itself was thought impossible because of the offshore Munda Bar, while to the south, Roviana Lagoon was thought to be too difficult to access by transports because of the barrier islands. Here there were two good beaches, however, and a deep water channel at Oniavisi. Strategically, Liana was much closer to Munda, but because it was rumored to be heavily defended, the Americans would eventually select Zanana, about 5 miles to the east. Subsequent events would prove these to be 5 of the longest miles American forces had ever faced.

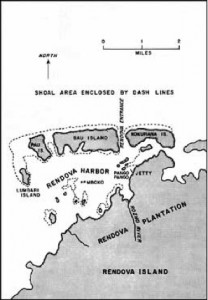

To cover the Roviana Lagoon landing, Turner & Staff decided to occupy Rendova. It was lightly defended, and its natural harbor offered good anchorages for PT Boats and various amphibious craft. Moreover, the outer islands (see map) provided solid coral footing for 105mm and 155mm artillery. Munda, only 7 miles away, was well within their range, so air strikes were no longer necessary to suppress its flight operations. Also, its 3400 ft. peak offered an ideal observation post out to a distance of about 20 miles. It would prove to be a smart move, although failure to take Arundel Island at the same time (see map) was a huge oversight.

The American Game Plan

Below is an excerpt of the Dog Day game plan, potentially a masterpiece of organizational confusion:

Rear Admiral Marc A. Mitscher who under Vice Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, Commander TF 33 and Air Force South Pacific, commanded the Solomon Islands Air Force, reported that 455 planes in his Force were ready to fly. These were 213 fighters, 170 light bombers and 72 heavy bombers. In contrast, the Japanese at Rabaul had but 66 bombers, and 83 fighter aircraft on this day, with an undetermined small number at Buka, Kahili, and Ballale, their three main operational airfields in the Northern Solomons.40

The main submarine unit of Task Force 72, commanded by Captain James Fife (1918), was Submarine Squadron Eight, commanded by Captain William N. Downes (1920). Captain Downes acted as Liaison Officer to Commander Third Fleet and was positioned in Noumea from the latter part of June until mid-July 1943. Six to eight submarines of this squadron were on station in the Solomons from mid-June to mid-July.

For Dog Day, the carrier task force was told to operate in an area nearly 500 miles south of Rendova–well out of range for any close air support and well clear of enemy shore based air.

One cruiser-destroyer force was assigned an operating area 300 miles south-southwest of Rendova, while another cruiser-destroyer-minelayer force was given the chore of laying a minefield 120 miles north of Rendova and bombarding various airfields north of New Georgia.

The planes from the escort aircraft carriers called “jeep” carriers41 were to be flown off to augment the shore-based aircraft of CTF 33, COMAIRSOPAC. One division of battleships was kept in a 2-hour ready status in far away Efate, 750 miles from the New Georgia objective.

AIRSOPAC would provide the aircraft umbrella, and the submarines would provide any unwelcome news of the approach of major units of the Japanese Fleet towards or past the Bismarck Barrier.

It should be noted that COMSOPAC’s Plan:

1. provided that a shore-based commander, Vice Admiral Halsey, retained immediate personal control of the operation.

2. did not provide for the coordination of the various SOPAC task forces under one commander in the operating or objective area, should a Japanese surface or carrier task force show up to threaten or attack the amphibious force, i.e., did not provide an Expeditionary Force Commander.

3. Did not provide any aircraft under the control of the Amphibious Task Force Commander for dawn or dusk search of the sea approaches immediately controlling the landing areas.

4. Did not provide in advance the conditions for the essential change of command from the Amphibious Task Force Commander to the Landing Force Commander, merely stating: “The forces of occupation in New Georgia Island will pass from command of CTF 31 on orders from COMSOPAC.”

—The Amphibians Came to Conquer, pp. 516-7

Opening Moves

After more than two months of delays, Toenails finally got underway on June 20th. First, Turner sent two companies of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion on a mission to Segi Point to rescue New Zealander Donald Kennedy, a long-time coastwatcher with a private army of about 200 Melanesian locals armed with captured Japanese weapons. Kennedy’s guerilla activities had so angered Gen. Sasaki that he had sent a company of infantry to hunt him down.

So the Raiders, some of Halsey’s very best troops, arrived for their sideshow on June 20th. Two additional APDs arrived the next day with a company of 103 Infantry Regiment and naval surveying specialists. No matter that Segi was some 30 miles from Munda, the main objective. The Seabee-built airstrip was of minimal effect in the campaign and was soon abandoned after the capture of Munda.

For June 30th, Turner & Staff had selected three additional points: Wickham Anchorage on Vangunu Island, just southeast of New Georgia; Viru Harbor, a short distance west of Segi Point; and Rendova Island, 7 miles south-southeast of Munda Point. Viru soon proved to be almost worthless as an anchorage, and Wickham was too far south.

Rendova was another matter. Here the landings, made by the Army’s 172nd Regimental Combat Team, plus a 105 mm artillery unit, were opposed by only 300 Japanese troops who were quickly subdued. Japanese coastal batteries near Munda made only a brief response before being silenced by American destroyer gunfire. Soon the 9th Marine Defense Battalion and two battalions of Army artillery arrived with longer range 155 mm guns. This would place Sasaki’s HQ on Kokengolo Hill (just behind the airfield) under constant attack, as well as the lower reaches of Kula Gulf.

Admiral Junichi Kusaka (11 Air Fleet in Rabaul) was not slow to respond. He flew off a raid with 24 Japanese Army bombers and 24 Army fighters joined by 20 Navy Zeros. The raiders flew in behind Rendova Peak and completely surprised the Americans, killing 59 men and destroying some of the newly-built structures. That night, light cruiser Yubari and 9 destroyers entered Blanche Channel from Blackett Strait and bombarded the new American base on Rendova. Fortunately their gunfire was inaccurate and no serious damage was done. PTs were sent to attack the Japanese, but the only ship they hit was American.

The venerable attack transport McCawley, Turner’s flagship since the beginning of “Watchtower,†had taken a torpedo from a G4M Betty bomber and was dead in the water. She had just finished debarking troops on Rendova and was heading down Blanche Channel when she was hit. Turner & Staff debarked onto a waiting destroyer, but the “Whacky Mac†finally met her end that night at the hands of some trigger-happy American PTs who mistook her for an enemy vessel.

July 4th saw the landing COL Harry Liversedge’s 2600-man Marine Raider Battalion at Rice Anchorage, about 15 miles north of Munda. They were brought in by 7 APDs, escorted by “Pug†Ainsworth’s three light cruisers and seven DDs. This relatively powerful force ran into a Japanese reinforcement group upon departing, and chased it away without landing any of its 1200 troops. Ainsworth had been bombarding Vila when the Japanese showed up. Unfortunately a Type 93 torpedo, launched from extreme range, fatally damaged destroyer Strong.

Meanwhile the American southern force began landing elements of General Hester’s 43rd Division at Zanana Beach on July 2nd. The balance of his troops would come ashore on July 5th.

At the End of the First Week

The American situation on New Georgia was as follows:

The American “Northern Forceâ€, the 2600 Marine Raiders, were ashore at Rice Anchorage, preparing to move south towards Enogai Inlet. They left behind two companies to guard their meager supplies and set off south down an existing jungle trail, carrying only three days rations.

The “Southern Force,†the Army’s 43rd Division, under command of Maj. Gen. John Hester, was ashore at Zanana Beach, preparing to drive west towards Laina and eventually Munda. The 43rd was an inexperienced National Guard division, composed of regiments from several states. By pre-arrangement, now that Hester was ashore he would assume overall command of land forces.

The Rendova occupation force was firmly in place and in the process of building a PT Boat base. In the often narrow waterways around the islands, it had been hoped that the PTs could deliver against Japanese surface ships and landing barges. Unfortunately they were to disappoint on many occasions.

The other American forces—at Segi Point, Viru and Wickham Anchorage—were, frankly, wasting their time in largely fruitless sideshows.

The American supply route was about 200 miles, unopposed from Guadalcanal, Tulagi and Purvis Bay. By July, Halsey/Turner enjoyed a large number of amphibious ships, LSTs, LCIs, LCTs and transports. Also, American air strength was steadily increasing in quality and quality.

The Japanese situation:

Sasaki had about 5000 men in the western part of New Georgia, concentrated in the “Dragon’s Head†area between Enogai and Bairoko, and in the Munda-Laina-Zanana area.

Sasaki’s immediate re-supply and replacement came via landing barges from Vila on Kolombangara, where there were about 10,000 soldiers at the time.

In truth, however, Sasaki’s supply line was nearly double that of his enemies, nearly 400 miles. Everything had to come down from Rabaul, usually via The Shortlands, Buin, Balale, and the like, then cross the Slot via destroyer transports and/or barge convoys to Kolombangara. Initially the IJN had sought to force its re-supply convoys right down Kula Gulf to Vila, but American reaction by Ainsworth’s force now had them thinking differently. Soon, the basic reinforcement strategy changed to sailing north of Kolombangara, close along the coast to hopefully confuse American radar, then making a southeast dash down the narrow Blackett Strait for a landing at Vila. From there, reinforcements and supplies went out in night time barge convoys to Bairoko, only about 20 miles to the southeast. The initial American failure to seize Arundel Island made this possible.

The landing barges—inevitably the 40 ft. steel-hulled Daihatsus, proved to be the key to Japan’s ability to prolong the campaign. Since Guadalcanal days the Americans had chiefly relied on destroyers to interdict barge traffic, but had met with only indifferent results; the small, maneuverable Daihatsus were simply too hard to hit with the DDs’ 5†main battery. Now in New Georgia, the waters at the bottom of Kula Gulf were too narrow to continually risk destroyers, so the PTs were put to work. Even up-armed with 40mm AA guns, the PTs were no great success, especially as the Daihatsus usually shot back at the unarmored plywood PTs. Not only did they carry their own armament of heavy machine guns, but the 70-odd soldiers aboard added to the defensive fire.

The Second and Third Weeks

In short order the southern force overland attack on Munda was bogging down. Hester’s inexperienced 43rd Division had been handed the most difficult terrain imaginable. They had to literally cut their way through the jungle with machetes and axes. This meant an almost single-file track where only a few snipers could delay the entire column. Fatally, Hester decided to split his forces, sending the 172nd Regiment to secure Laiana from the rear while the 169th Regiment continued its westward advance parallel to the coastline. The Japanese took advantage of this and attacked between the two regiments, even daring to assault Hester’s HQ. By July 9th Hester had been fought to a standstill.

Equally troubling was the great number of “combat fatigue†cases the 43rd was rapidly accumulating. Overstressed by the heat and the dampness, having to literally crawl up some of the ravines on all fours while always cutting away the vegetation, the Guardsmen were often terrorized at night by stealthy Japanese tactics. Fire discipline evaporated, and soldiers often took shots at imaginary targets and sometimes even their own comrades.

For the night of July 11-12 Halsey ordered Tip Merrill’s cruiser-destroyer force to hit the Japanese lines with a heavy bombardment. Hopefully this might break the stalemate. Accordingly, Merrill’s ships fired off some 8674 rounds of 5†and 6†shells in 40 minutes. Trouble was, the Army and the Marine Corps had very different views about naval and artillery bombardment of enemy positions. While the Marines generally welcomed close fire support, the 43rd Division did not, so Hester told Merrill not to fire closer than a mile from his positions.

So naturally the bombardment accomplished very little, and the Japanese were rewarded by a large margin of safety. For hours afterward bombardment was not followed up by an American attack, so its shock value was wasted. The next day, 172nd Regiment was still a half mile from Laiana when it was cut off from the 169th Regiment by Japanese infiltrators.

In the meantime 16 barges of reinforcements had reached Sasaki, and on the night of 12-13 July another 1200 troops were dispatched by destroyer-transports to New Georgia. Ainsworth was sent out to interdict this latest “Tokyo Express,†and the Battle of Kolombangara ensued. The Japanese lost a light cruiser (Jintsu, Admiral Tanaka’s famous old flagship from Guadalcanal days), the Americans a destroyer. Still, the Japanese managed to land their 1200 troops on Kolombangara

On the 14th the 172nd Regiment finally captured Laina, which allowed reinforcements be brought in over the beach, including a company of Marine light tanks. Trouble was, in the meantime Sasaki had dug in a battalion of troops between the 172nd and the hapless, exhausted 169th which had already suffered heavy casualties from friendly fire and combat fatigue.

Warning bells sounded at Halsey’s Noumea HQ. This operation was taking far too long and was in danger of throwing off the Pacific timetable, so XIV Corps Commander Maj. Gen. Oscar Griswold arrived to make an evaluation. He was Hester’s immediate superior, and as he learned of the Army’s multiple problems, he requested immediate reinforcements from Halsey.

He got his way, and two additional American divisions, the 25th and 39th, were on their way. Halsey also sent up his top Army commander, Lt. Gen. Millard Harmon (SOPAC Army Commander) to New Georgia with orders to do whatever was necessary to take Munda—and as soon as possible.

Immediately Harmon saw that new leadership was needed, and on July 15th Griswold was told to assume overall ground command, leaving poor Hester only in command of his 43rd Division. Also on this date “Ping†Wilkinson relieved Kelly Turner as commander of the amphibious force—now re-labeled III ‘Phib.

Unaware of the latest American changes, and newly reinforced by the arrival of a fresh regiment from Vila, Sasaki felt bold enough to launch a counterattack on July 17th. One Japanese regiment pinned down the 172nd while another sneaked around behind to cut the trail to Zanana. But Griswold had new cards to play; he sent the 148th Regiment to Zanana, and within a few days contact was reestablished with battered 169th Regiment.

Meanwhile, Liversedge’s Marine Raider force was attempting to cut communications between Munda and Vila. After a long slog through the jungle, on July 21 they finally received massive air support from 250 aircraft from Guadalcanal and drove Japanese out of Bairoko, finally cutting their supply line. On July 24 Liversedge was reinforced and resupplied by a convoy escorted by CDR Arleigh Burke. This gave the Raiders sufficient strength to hold their roadblocks, but not enougth to advance on Munda by the back door.

The Fourth Week

The Seabees had been hard at work building a corduroy road towards Munda, and on July 25 Griswold launched a new offensive. The 43rd and 37th Divisions led the assault, which began at dawn after Burke laid down a ferocious bombardment on the area in front of 43rd Division. Records show some 4000 rounds were fired at a density of 70 shells per 1000 square yards.

If this seems like a lot, it really wasn’t, and proved inadequate to root out the Japanese troops, some of whom escaped the bombardment by quickly moving as close as possible to the Americans. Afterwards, RADM Wilkinson led an investigation which concluded that 200 shells per 1000 square yards was required for complete neutralization of enemy troops in their coconut log bunkers, as only a direct hit was capable of taking them out.

As a result, the American attack that followed the bombardment made slow progress in spite of support from Marine M-5 light tanks, which found they could not traverse the hilly, muddy terrain. Bibilo Hill, cornerstone of Japanese resistance, did not fall until August 5th, when it was smothered with fire from mortars and artillery. After the fall of Sasaki’s HQ on nearby Kokengolo Hill, Japanese resistance collapsed and the Americans moved into Munda unopposed. Unknown to the Americans, Sasaki had ordered an evacuation to Vila two days earlier.

Endgame

Mop up of the last Japanese survivors continued until August 25th. On August 20th Baanga Island was captured after a bitter fight, and on August 24th Bairoko harbor was finally taken. On August 27th the 172nd Regiment landed on Arundel, the island on the south of Kula Gulf, repelling a strong counterattack from Vila on September 15th. Additional reinforcements were sent in and the island was finally cleared on September 20th —about 2 ½ months after it should have been.

Now as the New Georgia operation drew to a close, Frank Giliberto, a squad leader in the 2nd Battalion of the 169th, spoke for most of his regiment:

Our morale is at rock bottom. Our losses are quite high. The men in my squad would look at me with reproach in their eyes, as if to say, “Why are we the point squad again? Are we the only unit around?” I knew how frustrated they feel. How much longer will our luck last? What the hell are we doing on this two-bit island? Why, when the Japanese started shelling Munda Field from Baanga Island was no attempt made to engage the Japanese 120-mm gun positions, with all of those artillery guns we had at our disposal? Where was the Navy with their big guns? Where were our bombers? From my point of view, here in the middle of Baanga Island, I felt strongly that everything that’s happened thus far is one big screw-up by all the top brass, and we are left to suffer because of their screw-ups. The Navy for not being able to control the sea around us. The G-2s and S-2s with their intelligence reports. And our Army, Navy, and Marine air support that we seldom got. With all the artillery that is available to us, you would have thought that all these small islands would have been shelled before we would land on them.

—Into the Shadows Furious, pp. 351-2

Giliberto’s words would certainly have found sympathy from almost all the soldiers and Marines on New Georgia.

Did this make it all worthwhile? An F4-U Corsair in the first scheduled landing on the newly operational airstrip at Munda, August 14th. From this day until the establishment of fields at Cape Torokina on Bougainville about three months later, the Munda airstrip became the scene of intense activity as planes landed and took off in the campaign to reduce Rabaul.

The Next Step

With New Georgia finally in American hands, Halsey was now faced with the daunting challenge of invading nearby Kolombangara. American intelligence maintained there were nearly 10,000 Japanese troops there, so it was calculated that nearly 60,000 Americans would be needed to root them out. It was not a happy prospect. Halsey had already poured some 29,000 men into New Georgia against a scratch force of only 4-5,000 Japanese, and it had taken him several weeks longer than estimates had previously calculated. Definitely, offensives in the jungle against a determined enemy were very costly.

Kolombangara is an unusual geological structure. An almost perfectly round, 9-mile diameter island, it represents the cone of an extinct volcano reaching up to 5450 feet at the summit. The slopes have eroded into innumerable deep valleys, from where a resolute defender could exact a heavy toll on his enemy.

This was too much for Halsey, and he quickly made the decision to begin what came to be called “island hopping.†50 miles north of Munda was the weakly defended island of Vella Lavella. The Japanese had used it primarily as a landing barge terminal at Horianu, but little else.

“Ping†Wilkinson had, in effect, anticipated Halsey’s decision. With Munda not yet in American hands, on July 21st Wilkinson landed a mixed reconnaissance force by PT boat. Assisted by resident coast watchers, the men explored the island for six days without encountering any Japanese soldiers. The reconnaissance force determined that Barakoma, on the southeast coast, would be a good landing place, as well as a good spot for a future fighter strip.

Vella Lavella

Vella Lavella, appx. 11 by 18 miles in size, is the northernmost island of the New Georgia Group on the west side of The Slot. Mountainous and almost entirely covered in jungle, doubtless it would have been bypassed were it not for its proximity to Kolombangara and its substantial Japanese garrison.

On August 13 Wilkinson sent several PTs ahead to mark the Barakoma beaches for the landings. Despite several Japanese air attacks, the convoys of APDs, LCIs and LSTs got through to land about 4600 men under BGen Robert McClure. In the following weeks he would be steadily supplied and his Seabees were hard at work building the Barakoma airstrip. By the end of the month III ‘Phib would deliver to McClure a total of 6300 men and 8600 tons of supplies. It would be more than enough to get the job done.

At Rabaul, Japanese commanders ADM Kusaka and GEN Imamura decided against any counterlanding to oust the Americans. They did, however, establish a landing barge staging point at Horianu, on the northwest coast of the island and about 9 miles of the new American position. They intended to defend Horianu from land attack as a hedge for possible future countermoves. Almost immediately this provoked what was to be the indecisive “Action off Horianu†on August 18th.

By mid-September McClure had advanced up both coasts and smashed the Horianu barge depot, sending the 600 or so Japanese survivors fleeing to the north end of the island, At this point the New Zealand 32nd Division was brought in to do the mop up. They made a last stand near Warambari Bay, but not before ADM Kusaka decided to make an attempt at rescuing them. This would result in the naval action of Vella Lavella on October 6-7. Each side lost a destroyer, but while the Americans were conducting rescue operations for the men of the lost destroyer Chevalier, a Japanese subchaser group sneaked in and embarked 589 men from under the Americans’ noses.

Blockading Kolombangara

Realizing they had been bypassed, and were in the process of losing Vella Lavella, the Japanese now focused on evacuating their Kolombangara troops across the Slot to Choiseul, first stop on the way to Bougainville. With Vila now under American artillery range from Arundel Island, the Kolombangara point of departure was now Tuki Point on the north shore of the island. A coastal trail led from Vila to Tuki, and it was there that Gen. Sasaki and his surviving troops massed.

By the end of September almost all of the Japanese—figures vary but somewhere between 5-6000 troops—had been evacuated in the face of determined American efforts to stop them. Beginning on September 20th over 100 Daihatsus were sent out from Bougainville, timed to reach Tuki Point in the darkness of the moon. By October 5 the Japanese had completed their Kolombangara evacuation, rescuing 5400 men by barge and another 4000 by destroyer, including General Sasaki. In the process, they lost about a third of their barges and a thousand men

American efforts to halt this were generally unsuccessful, demonstrating once again that different methods and weapons would be required to deal with short-range Japanese troop movements by landing barge. Eventually somebody on Wilkinson’s staff hit upon the (then) novel idea of taking the humble LCI and arming it to the teeth with 40mm Bofors guns, 20mm Oerlikons and lots of .50 caliber machine guns; these were put to good use in the forthcoming operation at Cape Torokina/Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville. LCI (G)s (for gunboats) as they were called, had long loiter time, their shallow draft made them almost immune to torpedo attack, and they proved very useful in supporting landings throughout the balance of the Pacific War. Cheap and quick to build, the LCI(G)s were really the first Littoral Combat Ships.

A Final Thought

Probably no other amphibious campaign in history was as complex as the New Georgia campaign. Many other operations elsewhere included much greater numbers of men and machines; many others covered much vaster areas. But for sheer complexity of simultaneous operations and difficulty of geography on land and sea, none can match New Georgia.

Thrust into this was an American planning staff that was learning as it went, and was often a victim of its own over confidence and tendency to make things overly complex. (Think Yamamoto at Midway for a good comparison.) Hindsight reveals what they should—and should not—have done at various points of the battle. Here’s but one of many examples (from Morison):

The vault to Vella Lavella proved to be a poor example of leap-frog strategy, as compared with many later operations, because our seapower was still incapable of isolating Kolombangara. In the narrow seas of the Central Solomons, even nearer to Japanese bases up the Slot than Ironbottom Sound had been in 1942, control shifted every dawn and dusk. The Allies were improving their technique of night fighting by air and sea, but never could put a stop to the Tokyo Express runs of destroyers or to the Daihatsu barge line. Their utmost efforts to blockade Kolombangara never succeeded in sealing it off completely. The Japanese concentrated on withdrawing their garrison by late September, and most of it got out.

–Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, p. 329

By the end of 1943 New Georgia was off the front pages of Navy news. In the Solomons, Bougainville operations were well underway and apparently headed for a successful conclusion at Empress Augusta Bay. By war’s end, only New Georgia veterans would choose to remember it and very little would be written about this difficult chapter in Navy history.

References:

- Into the Shadows Furious: The World War II Assault on New Georgia by Brian Altobello; Presidio Press, 2000. 408 pgs.

- The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia (http://pwencycl.kgbudge.com/) © 2006-2009 by Kent G. Budge

- The Amphibians Came to Conquer, The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, by VADM George Dyer, Superintendent of Documents, 1973

- Munda Trail: The New Georgia Campaign June-August 1943, by Eric Hammel, Pacifica Press 2000

- Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, Vol. VI of History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, by Samuel Eliot Morison, Little, Brown, 1950

- Marines in the Central Solomons, by Maj. John M. Rentz USMCR, USMC Historical Section, 1952

Cross-posted at USNI Blog