Midway 70 Years Later: Forces in Motion

JAPAN – Citing Japanese victories in the Coral Sea and other battles, Radio Tokyo the previous day announces that “America and Britain… have now been exterminated. The British and American fleets cannot appear on the oceans.”

Around the world, forces were joined and movement was afoot in this truly global war. In Russia, the 2nd Battle of Karkhov was winding to a close. After initial Soviet successes and re-capture of the city, they now found themselves surrounded and an attempted breakout two days earlier had failed. Southward, in the Crimea, the Nazis have begun their summer offensive. In Africa, Rommel has undertaken an offensive against the British defensive positions at Gazala. In Britain, preparations are being made for the first thousand plane raid against Germany – American forces were just beginning to arrive under the command of Eighth Air Force, VIII Bomber Command, but would not see their first combat for another 2 months. In the China-Burma-India theater, 10th Air Force moved B-17’s of the 11th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 7th Bombardment Group (Heavy) from Karachi to Lahabad, India. In the Southwest Pacific Theater, 5th Air Force B-17′s bomb the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul; 8th FG P-39s intercept Japanese fighters attacking Port Moresby, Australia losing two P-39F’s in the process. And at CINCPAC HQ, Ed Layton answers a question from Nimitz – name the dates and dispositions the enemy intends to take up around Midway:

“‘I want you to be specific,’ Nimitz said, fixing me with his cool blue eyes. ‘After all, this is the job I have given you – to be the admiral commanding the Japanese forces, and tell me what is going on.’ It was a tall order, given that so much was speculation rather than hard fact. I knew that I would have to stick my neck out, but that was clearly what he wanted. Summarizing all my data, I told Nimitz that the carriers would probably attack on the morning of 4 June, from the north-west on a bearing of 325 degrees. They could be sighted at about 175 miles from Midway at around 0700 hours local time. On the strength of this estimate, Admiral Nimitz crossed his Rubicon on 27 May 1942…I knew very well the extent to which Nimitz had staked the fate of the Pacific Fleet on our estimates, and his own judgment, against those of Admiral King and his staff in Washington.†– …And I was There (Ed Layton) 1985, pg. 430.

Nimitz (l) and Layton (r)

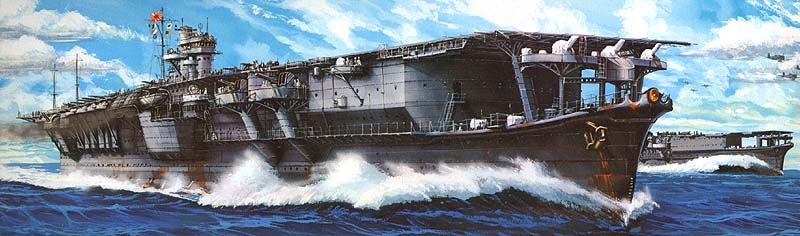

By May 30th many wheels were in motion. After clearing the Inland Sea on the 27th, Nagumo’s forces have set a north-easterly course at 14 knots. Ships crews turn to the daily routine of maintenance, cleaning and participating in drills while the embarked aircrew amused themselves playing cards in the ready room or passing around novels while sunning themselves on the flight deck – some had brought wooden deck chairs for this purpose. (ed – It would appear there were (are) some universal similarities across naval aviation down through the ages… – SJS). The overall mood of the crews was relaxed. Duty carrier rotation was set with Soryu taking the first watch on the 27th. However, overnight on the 27th, CDR Fuchida Mitsuo, CAG for Akagi’s air group, was diagnosed with acute appendicitis. Although he pleaded otherwise, the flight surgeon overruled him and operated immediately. Fuchida would miss leading the air group in battle, no small matter to the veteran crews. By 1430 local on the 28th Kido Butai’s supply ships are sighted and once they were joined in the force, a course change to east-northeast was ordered. Speed remained at 14 knots in consideration of the destroyers and other fuel hogs in the fleet.

Meanwhile, at Pearl Harbor the USS Yorktown arrived on the 27th bearing the evidence of the savage action from Coral Sea. Grievously wounded by both direct-hits and near-misses (even while having avoided a spread of eight air-launched torpedoes), Yorktown required at least a three month overhaul and refit. However, Nimitz knew Yorktown was the only carrier available to add to the task force that had previously sailed on the 27th, comprised of Hornet and Enterprise. Two carriers against Kido Butai would not be sufficient – Saratoga, enroute from the West Coast, would not arrive until 7 Jun, too late to be of use. Ranger was otherwise engaged and Lexington, well, Lexington was lost after a valiant fight at Coral Sea. The third carrier had to be Yorktown.

When she entered Pearl on the 27th, over 1,400 shipyard workers swarmed aboard and immediately set to work repairing the damage, along with ship’s company. On 28 May she entered dry dock to repair cracks in the hull and fuel holding tanks from the near misses. In forty-eight hours another in a series of miracles ensued and Yorktown made ready for sea. At 0900L 30 May 1942, Yorktown put to sea, her airwing replenished with three of Saratoga’s squadrons (VB-3, VF-3 and VT-3 replacing VS-5, VF-42 and VT-5, all of which had suffered heavy losses at Coral Sea). How significant was this action? In a word – it was pivotal. The urgency to turnaround Yorktown, bring aboard squadrons who had never operated off her before and in so doing, get a third carrier into action was one of the key points in the outcome of the coming battle – and make no mistake everyone from Nimitz down to the newest seaman on the Yorktown knew it. This was in studied contrast to the almost leisurely approach the Japanese took in repairing Zuikaku and replenishing her air wing (the Japanese did not rotate airwings between carriers and didn’t think about doing it until later in the war).