Shashou Jiang: Ballistic Missiles vs. CSGs (Pt II)

To summarize from Part I – a Chinese strike using Theater BM’s has been conducted against two American CSGs enroute to the Taiwan Straits as a show of US resolve and support to Taiwan during another brewing cross straits crisis. The strikes garnered mixed results, with the loss of two support ships and minor damage to a few destroyers in the GW CSG and extensive damage to the Reagan – akin to what the

Discussion

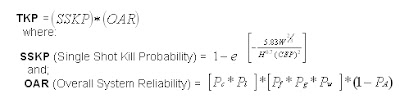

In scenario play, it’s easy to make the enemy’s weapons always lethal, remove/reduce gaps in intelligence and every decision is on time and the right one. Conversely, one can also make every defensive countermeasure 100% successful too… In view of that concern, just how plausible is this scenario? A simple model using Terminal Kill Potential (TKP) follows. TKP is the determination of the military threat potential of a weapons systems and is found through the following equations:

The Pk of any system is a function of the multiplication of the probability of success of each of its subcomponents — the more subcomponents and the more challenging flight environment, the lower the Pk will be. Even assuming an overly optimistic 99.9% probability of success for countdown (c), launch (l), flight and re-entry (f), guidance (g) and warhead reliability (w), the OAR for this system yields a 99.5% reliability unopposed – add an ABM system (1-PA ) that is only 75% reliable and the OAR plummets to 25%. Assuming a nuclear warhead (for which this calculus was derived) with a small yield (150 KT) and a CEP of 3000 yds, the SSKP = 1.0 (assuming a “soft” target – overpressure of 3.6 psi to kill) and yields a TKP of .995 (unopposed) or .248 (vs. an ABM system).(1) With conventional, chemical or biological warheads TKP would face further challenges (active seeker reliability, dispersion of submunitions, etc). The number of variables that can be injected are mind-numbing, everything from impact of weather to LO or ‘stealth’ measures taken by the target to something as seemingly mundane as a back-up generator that has a history of injecting power surges prior to shutting itself down – all have an impact on the reliability and hence, the probability of kill by a system. TKP can be substantially enhanced by employment of large numbers of conventionally armed missiles.

As laid out above, there are many hurdles the Chinese would have to overcome to effectively conduct anti-CSG strikes with shore-based TBMs. Consider the target – the CVN’s at the core of the CSG. Critics of big-deck carriers regularly make reference to their inherent size and hence, alleged ease to target. True enough, in benign conditions and with a cooperative target, carriers can be readily located and targeted. This becomes an especially problematic issue if a carrier has to operate close to shore or in restrictive waters as it narrows the range of possibilities the opponent must consider in setting up a search plan.

In the above scenario you had two different situations – one CSG in relatively open ocean, proceeding in a formation that provides for mutual support, but widely dispersed owing to networked sensors and communications. This CSG has the sea room, coupled with advance warning to complicate the target acquisition phase in the terminal stages of the TBM strike. Consider – a modern CVN can make in excess of 25 knots. Big deal you say? 25 knots is what, 28 – 29 mph? What does that buy? It means in one hour the carrier has moved 25 nautical miles from its starting point. Yes, but the time of flight of a ballistic missile (in this scenario) is about 20 minutes, you reply. At 25 knots, a carrier will cover roughly 800+ yards every minute – 8 football fields per minute. In 20 minutes it will have moved 16,000 yards or 8 nm. There is enough error induced such that a non-maneuvering, conventional RV could conceivably miss wide of the mark, especially if a course change is cross range (perpendicular) to the ballistic missile’s path. Remember, once launched there is a minimal amount of maneuver a ballistic missile may engage in – the target coordinates will generally not be updated and it will likely end up delivering its payload to open ocean.

A MaRV improves the probability of a strike though. With a terminal detection capability (radar, IR, anti-radiation) that error may be reduced – if the target is detected in enough time in the terminal phase. Generally speaking, one can expect a MaRV to be flying at about Mach 8 endoatmospherically. Owing to the construct of the RV, payload weight penalties, speed and thermal effects, the terminal seeker will necessarily have a limited field of view. If the target falls outside the field of view, the warhead subsequently has a PK of 0, especially if it is a unitary device. If the target does fall in the Filed of View (FoV), there still may be aerodynamic limits on the RV’s ability to maneuver. There are two options to reduce the impact of targeting uncertainty in this scenario – use “smart” submunitions or go nuclear. The latter, particularly in an airburst mode, would be effective up to certain ranges/yields. To a country looking to terminate another’s course of action while minimizing the possibility of escalation though, nuclear weapons are generally not the first round of choice. Smart submunitions, on the other hand, have proved themselves effective against a variety of soft and semi-hardened targets under actual combat conditions for some time now. By 2015, the technology involved in miniaturization of submunition seekers should promote the use of a variety of sensor types to be carried in one RV payload as well as the number of submunitions.

Open ocean surveillance is platform- and time intensive. Substantial resources can and usually are spent in this endeavor. A threat that goes unlocated ramps that effort up even more – just ask the Soviets about efforts to find a CVBG in the

Similarly, on the defensive side challenges abound. A kinetic kill vehicle-based missile defense would be challenged in several areas. Target cuing, tracking, reporting, acquisition and intercept would provide several avenues of approach for counter-measures. Balloon decoys, chaff, jamming – all the penetration aids presently used on strategic missiles would be employed in an attack launched by MR/IRBMs. Using different radar types and frequencies helps sort through the decoys to uncover the warhead.

So what is the plausibility of the above? Is

Nice piece! But may I bring up a few points that I think may not be accurate? I believe that chaff would not be a viable PENAID? And jammers would not likely find any place on board a weight and volume limited warhead. Decoys are available, but they detract from payload capability. Also, the maneuvering capability of MaRVs were not to evade ABMs, but to increase accuracy.

Finally, I think you should have elaborated on the extreme difficulties in warhead terminal guidance, considering its extreme re-entry speed, seeker range and search speed limits as well as limited MaRV maneuverability.

1. Chaff very much is a viable PENAID in the mid-course portion of the trajectory in that it obscures or complicates the abilty to locate and discriminate the warhead, ditto inflatable decoys that utilize jammers and IR decoys – the size/weight of the former are considerably smaller and lighter now as efforts in the airborne arena would attest to. Additionally, debris from the booster airframe, shroud, etc adds to the confusion. Concur with the payload tradeoff – but it is the classic creative tension between offensive payload vs. defensive measures to ensure delivery of the payload. The advent of smaller/”lighter” physics packages, improved accuracy and booster throw-weight led to the inclusion of PENAIDS as part fo the bus configuration for MIRVd ICBMs. The Chevaliar PENAID system employed on the British versions fothe Polaris SLBM (one of the earliest documents uses of PENAIDS) would look like a schoolbus compared to a compact sedan were it to be compared with today’s PENAID packages. As to the ability of avoiding ABM defenses, infact the first MaRVs were designed explicitly for that purpose. Something as simple as a “cranked” aeroshell that would impart a terminal maneuver owing solely to aerodynamics at a certain speed range int he atmosphere was employed early in the MIRV process. It was only later, with smaller guidance computers and terminal seekers that a MaRV employing a terminal seeker could become a viable weapon – viz. Pershing II

2. Comes a point (as laid out in part I of the articles) where the trade-off for detailed discussion on highly technical/esoteric topics and maintaining a large readership base tend to diverge whilst rapidly closing on the boundaries of what can be discussed in an open forum. But thanks for the comments just the same 🙂

– SJS

terminal point defense is not impossible. if enuf guns can fire together, they will destroy the RV. but agree that the KE effects from the debris will still be substantial.

have some issues with the scenario, politically speaking. attacking Guam and Kadena is substantially different from striking a CSG at sea. attacking a CSG means that China does not cross the bright line of land territory, whereas attacking Guam will definitely cause the US to escalate and may lead to general, though conventional, war. Definitely would thus allow the US to retaliate on Chinese launch sites.

Attacking Kadena, tho an US AFB, would also draw Japan directly into the fight.

Agree that is the most dangerous Red COA, tho.

Couple of points:

1. Terminal defense against a hypersonic RV with CIWS or a CIWS derivative has a very low Pes, close to 0 as the kill mechanism is purely kinetic (talk about shooting a bullet with a bullet). Lots of other issues too like duty cycle on the gun, lateral tracking vs. crossing speed by the RV, etc. And while a (theoretical) laser weapon might meet the duty cycle and energy on target requirments, what would be the kill mechanism? Time is a critical element (not just detection, but also illumination time) – would the kill mechanism be ablating enough of the RV’s surface to induce an asymetric aerodynamic load, throwing it off course and possibly causing it to breakup because of the loads? Maybe – but given the thermal event it just went through, and the hardening implcit in an RV, just how many joules does one need to put on the beast and for how long? You could be illuminating it all the way up to impact…

2. Like most scenarios, this one is heavily caveated – the intent was to look at two situations for the CSG: maneuvering and not and exlpore a capability across a given range using areas familiar to the reader, not delve into larger geo-political questions. An alternative to the Guam portion might be a CVOA in international waters where the CV is constrained to a fixed geolocation because of the short legs of its strike aircraft and distance to the target areas…

Shoot – it’s a pretty widely accepted deal that during the Cold War the expectation was the Soviets were going to seed the CENT/East Med with nukes off IR/ICBMs to kill the CV’s operating there. Guess that was the original ASBM, eh? 😎

– SJS

Hey. I got a 502 gateway error earlier today when I tried to access this page. Anyone else had the problem?

Up and running now…