Flightdeck Friday: TFX — A Time for Turkeys (Pt I)

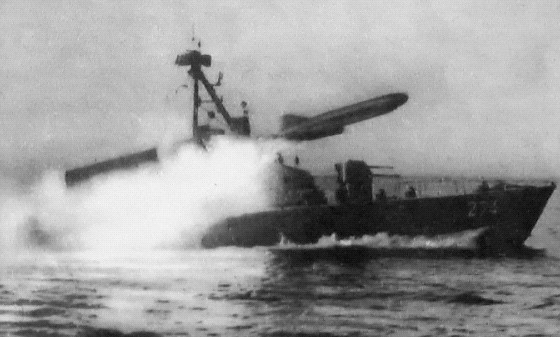

1959. Changes are afoot in the tactical aircraft programs for Air Force and Navy’s specific requirements. The Air Force sought to replace the F-105 with a new fighter-bomber that would address the shortcomings of the Thunderchief — it was to land in half the distance of the F-105, be able to fly unrefueled to Europe or Southeast Asia (the latter with one refueling), have a tree-top dash capability of 900 kts for 400 nm and a high altitude dash speed of 1400+ kts. By 1960, these requirements were formalized in TAC’s Specific Operational Requirement Number 183. On the Navy’s side, the prospect of facing large raids of missile carrying aircraft in the near future led to the requirement for a missile carrying platform that would engage the raids at long-range. In combination with the new F4H-1 Phantom, in prototype stage, the Fleet Air Defense mission would be satisfied with this combination of fast-climbing/high-speed interceptor carrying short and medium range missiles to intercept any leakers that made it through the barrier established by the long-range missiles launched from their carrier.

Early in the process it was evident that there were more than just competing design requirements at work. Even the processes by which the Navy and Air Force sought to develop and build new aircraft differed. The Navy selected a contractor on the basis of their design — major changes were not contemplated. In fact, a requirement for a major change was used to eliminate designs from further consideration under this process. The Air Force, on the other hand, continually emphasized that their procedure was “source selection” not “design selection.” As such, it was considered normal practice by the Air Force to make major changes in designs after a source is selected. In a memo for the record, written in January 1963, George Spanberg (BuAer) explained the divergent processes further when moving to final selection:

“Air Force methodology is quite formal with written criteria established by the Source Selection Board, against which an evaluation group rates all proposals numerically. Raw score ratings are adjusted in accordance with a previously prepared weighting schedule by the SSB. Voting members of the SSB, after a briefing by the Evaluation Group, prepare a written recommendation through the Air Force Command structure to the Air Force Council. The Council recommends a decision to the Chief of Staff and to the Secretary. All recommendations are closely held with no feedback to lower levels. The briefings remain basically unchanged from the SSB through the Secretarial level and necessarily contain no conclusions or recommendations, since the presenters are not privy to that information. In a Navy design competition on the other hand, experience is substituted for formality, designs are evaluated, conclusions drawn and recommendations presented by the working level through all review levels. The source decision is the responsibility of the Chief, BuWeps who normally obtains concurrences from OP-05 and the Secretarial level. Reversal of source decisions by higher authority had not occurred prior to the recent VTOL program.”

All of which laid ground for the controversies that followed over design and manufacturer. Navy held fast to their belief that the FAD requirements were incompatible with the Air Force’s tree-top Mach dash requirement (which they held just as strongly to). In the meantime, politics was beginning to be interjected into the program with the cancellation of the Bendix-designed AAM-N-10 Eagle. All of this was background to the issuance of the first RFP in late 1961. Nine manufacturers eventually responded (Northrop was the only major firm to decline to submit a bid) and the proposals from Boeing and General Dynamics (teamed with Grumman), both utilizing a swing-wing, were considered the best, albeit still short of the RFP. Over the course of the next year a pitched battle would be waged between Boeing, generally held to have the best design by the two Services, and the GD-Grumman team. Three subsequent proposals continued to refine the process, but still both manufacturers’ designs fell short. Politics also entered the fray as the delegations from Texas (home of GD and the now terminated B-58 production line) and Kansas (Boeing’s Wichita plant which produced the B-52, a line now also closed) weighed in as well.

By August McNamara was tired of the back and forth and ordered a final competition between Boeing and GD based on a point system for categories based on performance, cost, and commonality. Boeing and General Dynamics resubmitted their final proposals in September of 1962. The Air Force Council, the Air Force Logistics Command, and the Bureau of Naval Weapons (which had replaced BuAer 1959) all indicated that they preferred the Boeing design, but on November 24, 1962 the Defense Department announced that the General Dynamics design had been selected. The reason given for the selection of the General Dynamics proposal was its promised greater degree of commonality and its more realistic approach to the cost problem.

And all hell broke loose.

With Senator Henry “Scoop†Jackson leading the fray in Congress, a series of congressional investigations was initiated, and the TFX stayed in the headlines for many months. Nevertheless, the decision of the Secretary stood, and the contract remained with General Dynamics. As a contemporary article in Time observed:

“The TFX award was a signal victory for General Dynamics’ President Roger Lewis. 50, who took charge last February after the company had lost a staggering $143 million in 1961. Lewis, a onetime Assistant Secretary of the Air Force (1953-55), has tightened operations and tugged GD back into the black. On TFX he got some help from that charming, arm-twisting Texan, Lyndon Baines Johnson. Pentagon insiders now refer to the TFX as the LBJ.”

Another factor was that Loser Boeing could not poor-mouth very effectively. With its plum contracts involving the Minuteman missile, the Saturn booster and the modernization of older B-52s. Boeing has enough work to keep its Wichita plant going. Boeing has also developed the X20 Dyna-Soar, the first fully maneuverable spacecraft. If the Air Force wins its fight for a military role in space. Boeing’s Dyna-Soar could supersede the TFX on some yonder tomorrow.

Next: Part II: TFX Takes Wing or “God as my witness, I thought turkeys could fly”

I still get a kick out of Adm. Connelly’s comment in front of the Armed Services comittee….. “Congressman…there’s not enough thrust in all of Christendom to turn that turd into a fighter”…..or something to that effect.

Aw, no don’t spoil part II 😉

– SJS

Heh, looking forward to part II. That whole debacle is probably the closest real life recreation of the WKRP turkey toss.

Re: Part II: TFX Takes Wing or “God as my witness, I thought turkeys could flyâ€

SJS, you’re not kissing up to CAPT Lex, are you? 😆

Hummer folk don’t kiss up to no one … 😉

– SJS