Flightdeck Friday: Beginnings – The Curtiss N-9 and BuAer

Hi all – this is the first post the Scribe wanted me to put up for you all. He’s always muttering up us kids and needing to ‘know our roots.’ So when all us apprentices started pulling his beard about being around since Methusela, well, he kinda went all Old Testament on us apprentices and made us do a write-up on the first aircraft contracted for by the Navy and something called the "Bureau of Aeronautics," both of which, coincidentily, had their start on this date. His last words to us on the way out the door was something along the lines of

"…kids! Buy ’em books, send ’em to school and all they do is tear out the pages and chew on the bindings…"

"…kids! Buy ’em books, send ’em to school and all they do is tear out the pages and chew on the bindings…"

So, okay Pops, here’s your article for today. /s/ Steeljaw Apprentice

On this date in 1916, the Navy contracted for its first aircraft, what would become the Curtiss N-9 via a telegram to Glenn H. Curtiss requesting that he “call at the Bureau [Construction and Repair] Monday with a proposition to supply at the earliest date practicable thirty school hydro aeroplanes.” Specified characteristics included:

- two seats,

- loading of about four pounds per square foot,

- and power loading of about twenty pounds per horsepower.

The telegram concluded, “Speed, climb and details of construction to be proposed by you. Rate of delivery is important and must be guaranteed.”

This telegram resulted in a contract for thirty N-9s which were delivered between November 1916 and February 1917.

(The following is from the Smithsonian’s write-up of the N-9. –SJA)

The Curtiss N-9 was a seaplane version of the famous Curtiss JN-4 trainer used by the U.S. Air Service during the First World War. To make the conversion, a single large central pontoon was mounted below the fuselage, with a small float fitted under each wingtip. These changes required a ten-foot increase in wingspan to compensate for the additional weight. Further modifications to the standard Curtiss JN-4 design were required to cope with stability problems that emerged in the N-9. They included lengthening the fuselage, increasing the area of the tail surfaces, and installing stabilizing fins on the top of the upper wing. The N-9 was initially powered by a 100-horsepower Curtiss OXX-6 engine. The U.S. Navy made use of wind tunnel data developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in its redesign the JN-4. The N-9 was the first U.S. Naval aircraft to incorporate wind tunnel data directly into its design.

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company of Garden City, N.Y., received a Navy contract for thirty N-9s in August 1916. Another fourteen were ordered by the U.S. Army, as it was also conducting seaplane operations at that time. The 100-horsepower N-9 was satisfactory for pilot training, but it lacked the performance needed for bombing operations and gunnery training. To meet these requirements, Curtiss replaced the OXX-6 with a 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza, then being manufactured under license in the United States by the Simplex Division of the Wright-Martin Company, and later by Wright Aeronautical Corporation. This improved model was designated N-9H.

A total of 560 N-9s were manufactured for the Navy during the First World War. Most of them were the Hispano-Suiza-powered N-9H model. Of these, only 100 were built by Curtiss. The majority were produced under license by the Burgess Company of Marblehead, Massachusetts. An additional 50 were assembled after the war by the Navy at the Pensacola Naval Air Station from spare components and engines.

During the war, 2,500 Navy pilots were trained on the N-9. In addition to training a generation of Navy pilots, the N-9 was used to develop tactics for ship-borne aircraft operations in 1916 and 1917, using catapults mounted on armored cruisers. After the war, the N-9 was again employed to successfully demonstrate a compressed air turntable catapult. This type of catapult was later installed on battleships, replacing turret-mounted platforms for launching aircraft. In July 1917, several N-9s were acquired by the Sperry Gyroscope Company and were used as test vehicles for aerial torpedo experiments conducted for the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance. The N-9 was withdrawn from the U.S. Navy inventory in 1927 after ten years of exemplary service.

The Bureau of Aeronautics

Also on this date, but in 1921, the Bureau of Aeronautics was formed. Established by an act of Congress in 1921, BuAer (as it came to be called) was created to bring order to the chaos that was procurement of naval aircraft and provide a single organization responsible for overseeing naval aviation. Prior to 1921, cognizance for aviation had been divided among various Navy bureaus and other organizations. The first Chief of BuAer was Rear Admiral William A. Moffett (1869-1933), a Medal of Honor winner and battleship commander who had long supported the development of Naval Aviation. He served as bureau chief from 1921 until his untimely death in 1933, in the crash of the airship USS Akron (ZRS-4).

A talented administrator, Moffett ensured the continued independence of Naval Aviation during the 1920’s, when Army Brig. Gen. William "Billy" Mitchell and others sought to merge all U.S. military aviation into a single, independent air force. Upon Moffett’s death, he was succeeded as Chief, BuAer, by Rear Admiral Ernest J. King–a future Fleet Admiral and Chief of Naval Operations during World War II. Other important bureau chiefs included Rear Admiral John S. McCain, Sr., the grandfather of U.S. Senator John S. McCain III (R-Ariz.).

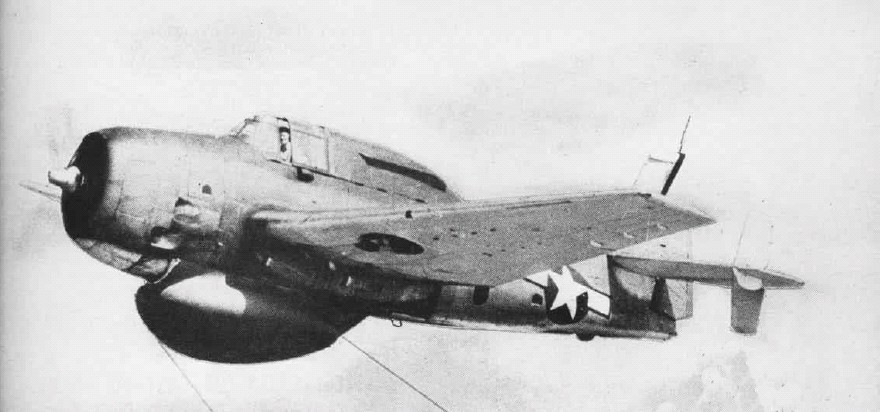

During the 1930’s, BuAer presided over rapid technological change in Naval aircraft. The bureau’s policy was to limit its own production, in order to support the civilian aircraft industry. BuAer used the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as a facility for building small numbers of prototype aircraft. While this effort yielded mixed results from the 1930’s (think of the TBD and Buffalo) it also led to the development of the Dauntless, Wildcat and Hellcat.

So how’d we do Pops? -SJA

A. Don’t call me Pops…!

B. Stay away from the Mustang, I’ve got the mileage written down…

-SJS (kids!)

See what happens when you toss them the keys and say: “Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do?”

SJSA – BZ…I assume more are writing is coming?