The Solomons Campaign: WATCHTOWER — Why Guadalcanal?

Next Friday, 7 August, is the 67th anniversary of the amphibious assault on Guadalcanal – the first halting offensive steps in the Pacific war. This week once again, UltimaRatioRegis joins the project with a look into the background of WATCHTOWER, setting the stage for next week’s post. The following week – Savo Island. – SJS

In the aftermath of a desperate and decisive battle, those of us who look back across the years, decades, and centuries at such events, inevitably ask the question; “Why there? What made that place worth the price in sweat, blood, and sacrifice?†Something must have drawn the crosshairs of history to such a place, made its possession worth the titanic struggle for control.

Megiddo, the most fought-over place on earth, is a hillock that dominates the ancient Haifa road in modern-day Israel. Such a symbol is it of man’s propensity for war that its very name is where scripture ascribes the end of the world to occur- Har Megiddo. Armageddon.

Gettysburg’s extensive road and rail junctions were keys to Robert E. Lee’s successful foray into Pennsylvania, once the Federal Army of the Potomac could be dislodged from the dominating high ground east of the town.

The terrain of Gallipoli overlooks the Dardanelles, and access to the Bosporus and the Black Sea, and was envisioned as a way to break the ghastly stalemate on the Western Front that had been consuming Europe’s youth for a year.

The Battle for Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands Campaign is no different. Except that by the Summer of 1942, it was not just what nature had made, but also what man had built, that drew the respective armies and navies into the fiery maelstrom that churned the jungle and the waters around them some sixty-seven years ago. As author Eric Hammel states; “There was no reason inherent in the value of the Bismarcks and the Solomons that made them worth a fight. Only a confluence of events would make them a focal point for a desperate gamble.â€(1)

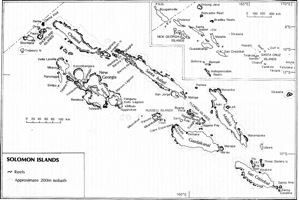

Those events began in the immediate wake of the First World War. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, who commanded the Grand Fleet at Jutland and became Governor-General of New Zealand, conducted an inspection tour of the Empire’s Pacific Dominions in 1919. Among the places which caught the Admiral’s eye as an important element to the defense of Australia was a magnificent natural harbor on the small island of Tulagi, tucked in the Sealark Channel in the southern Solomon Island chain.(2) However, in the post-war Empire, large expenditures in preparation for the next war were not among the priorities of the weary and battered British government. So, aside from the commercial exploitation of this area of what was still the British Solomons, no military preparation of the harbor at Tulagi took place.

In the 1930s, Japan began a secret effort to build fortified bases in the Caroline and Marshall Islands, in direct contravention of the Mandate that ceded them to her from a defeated Germany in 1918. Truk, the massive Japanese Navy base in the Caroline Islands, was a part of what Imperial planners conceived as a series of strongpoints that would form a defensive “belt†against US and British intervention while the Japanese Army and Navy completed the conquest of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The pre-emptive strike on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, and the invasion of Wake and the Philippines, along with the push into Singapore and Hong Kong, effectively eliminated any Allied ability to oppose Japanese expansion for many months. But not as many months as the Japanese required.

In January of 1942, Japan occupied Rabaul on New Britain, eventually building yet another very strong Naval and air installation whose position was problematic to the Allies in maintaining communication with Australia. The severing of the very tenuous line of communication between the United States and Australia was the goal of a thrust across the northern islands and waters of New Guinea, New Britain, and the Solomons. The Japanese plan, code-named “FSâ€, was an attempt to put a stranglehold on Australia as the staging area for the buildup of US forces in the Pacific.

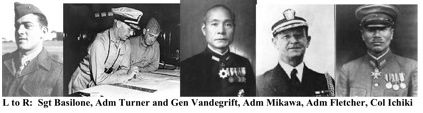

On 3 May, 1942, the Japanese occupied Tulagi (3), and began construction of a seaplane base and supporting infrastructure that would imperil Australia, New Zealand, and the New Hebrides, America’s main link to her allies still in the fight in the Pacific.

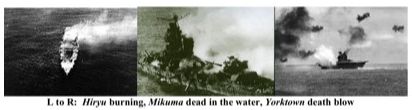

Concurrent with the occupation of Tulagi, the Combined Fleet thrust southeast with the intent of capturing Port Moresby, on the southern tip of New Guinea, gravely threatening not only the lines of communication with Australia, but Australia herself. The Japanese thrust was parried by US Navy forces under Admiral Fletcher at The Battle of the Coral Sea on 7 and 8 May, 1942. The battle was damaging to both sides, and included the sinking of the large US carrier Lexington and severe damage to Yorktown, and the loss of nearly 70 aircraft. (The Japanese efforts to take Port Moresby shifted to an advance over the forbidding Owen-Stanley mountain range via the Kokoda Trail in central New Guinea, which would result in a severe setback for Japan and heavy casualties among her forces.)

In early June, Nimitz’s gamble regarding Japanese intentions paid off with the decisive victory at Midway, where smaller US forces inflicted devastating damage to the Japanese invasion fleet, sinking four fleet carriers for the sinking of patched-up Yorktown. Plan “FS†was cancelled, as the Japanese were weakened by the loss of so many aircraft and trained pilots, more than 400 in all, and five carriers, at Coral Sea and Midway.(4) Though the victory at Midway went far toward evening the odds between the Japanese and the US Pacific Fleet, the advantage in combat power, surface and air, remained squarely with the Japanese. However, Midway provided an opportunity for the Allies to seize the initiative in the Pacific. Admiral Ernest King demanded action to do just that.

Elsewhere in the summer of 1942, the United States had been deeply disappointed that Britain did not believe a cross-channel invasion of Europe was possible during that year. The British experience in France in 1940, and throughout the North Africa campaign, had showed what a skilled and powerful enemy the German foe was. Churchill and the Brits, with the debacle of Dieppe fresh in their minds, dissuaded their overeager American allies from the foolishness of attempting a 1942 cross-Channel invasion. The Americans saw the opportunity to turn more of a focus to the Pacific Theater, at least temporarily, with the much smaller North Africa landings taking the place of the desired France adventure. The timetable of a thrust by the Allies in the Pacific scheduled for the autumn of 1942 was moved up. Following Midway, the Japanese were off balance, stretched thinly through Rabaul and New Britain. Admiral King demanded an offensive beginning in the mid-summer of 1942. (5)

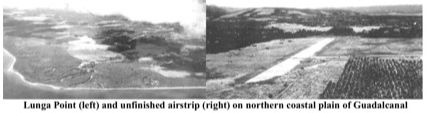

But for the US planners, the question was: where to strike? Some time in June, 1942, Japanese engineers had crossed the Sealark Channel to the larger island to the south, Guadalcanal. Specifically, the engineers surveyed the northern coastal plane of the island, and found it suitable for the construction of an airfield. If such a facility could be constructed there, combined with the harbor at Tulagi built up to provide an anchorage for Japanese warships, a powerful base akin to Rabaul would sit directly astride of the lines of communication between the United States and Australia. Such a situation would make the predicted American buildup of combat forces in Australia a slow, difficult, and costly process, just as “FS†had hoped to do.

In the Pacific, both MacArthur and Nimitz thought it prudent to secure and defend the lines of communication with Australia, and evict the Japanese from the areas that threatened those lines. MacArthur’s first suggestion, a direct assault on Rabaul, was quickly dismissed as unfeasible once cooler heads prevailed. Instead, a thrust into the lower Solomons, to include seizure of Tulagi and Santa Cruz, would be the first step in reducing the threat to Australia. From there, the effort would include the recapture of the northern coast of New Guinea, and eventually, reduction and capture of Rabaul. On 10 July, Nimitz issued his operations order for the attack and seizure of Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The operation’s codename was WATCHTOWER, and was scheduled for execution on 1 August, 1942.

In mid-July, a USAAF B-17 reconnaissance aircraft carrying Col Merrill Twining, 1st Marine Division D-3 (operations officer) overflew Lunga Point, but could not verify the Japanese airfield construction efforts reported by the network of Coastwatchers that kept the Japanese under constant observation.(6) But photography of the beaches surrounding Lunga Point provided the assurance that those beaches were without obstacles, and suitable for an amphibious assault. Detailed planning then began in earnest for WATCHTOWER.

And so it would be that this as-yet incomplete airfield on the coastal plain, surrounded by jungle, on an island nobody had ever heard of, in an island chain few could find on a map, would become the focus of a massive struggle which would ebb and flow across the skies, land, and seas for eight months. The campaign would decide whether the Americans were able to seize and retain the initiative in the Pacific, or whether the Japanese, after the briefest of pauses, would continue what had seemed an inexorable string of conquests to the final defeat of the United States and her allies.

The names and places on the island itself, and those of the surrounding islands and waters: Guadalcanal, Savo, Ironbottom Sound, Tassafaronga, Edson’s Ridge, Henderson Field, The Slot, Santa Cruz, Tulagi, Ternaru, Matanikau, Lunga Point. Unknown but for a “confluence of eventsâ€, those places and the men who fought there with such grim determination, have been immortalized in the legends of the United States Navy and Marine Corps.

______________

(1) Guadalcanal; Starvation Island, Hammel, Eric, Crown Press, pg xxxi.

(2) The Guadalcanal Campaign, Maj Zimmerman, John L, USMCR, USMC Historical Branch, 1949, pg 1.

(3) FMFRP 12-109-1, The Amphibians Came to Conquer, VADM G. C. Dyer, USN (Ret.), 1969 USMC republication, 1991, pg 255.

(4) Guadalcanal, Frank, Richard B., Penguin Press, 1990, pg 43.

(5) The Old Breed, McMillan, George, Infantry Journal Press, 1949, pg 17.

(6) The Guadalcanal Campaign, Zimmerman, pg 16-17.

I cannot begin to tell you how much I appreciate this, and all of your different series on WW II battle history.

As an armature Pacific theater buff (vs. historian) I find your posts invaluable.

It is your post on Midway that introduced me to Shattered Sword, which answered many of the questions I have had since I was a kid in the 50’s and 60’s.

It’s like sitting on the edge of my seat, waiting for the next episode!

Thanks so much!

Very nice setting of the stage. I did a Google Earth of the ‘Canal the other day and what struck me more than previously was the size of the island and how mountainous the terrain quickly becomes once south of Bloody Ridge. It only heightens my appreciation for the incredible challenges faced by the combatants. I look forward to more.

VR,

Andy