Flightdeck Friday: The YF4H-1 Phantom II – Operations Skyburner and Sageburner

Standby; standby; mark”

In the relative cool of the early dawn, remote recording equipment began timing the grey and orange streak that thundered by at 125 ft above the desert floor. The date is 28 August 1961 and a second attempt at the world’s low altitude speed record is underway. Flying a 3km closed course on the grounds of Holloman AFB, NM is the future of carrier-based interceptors: the YF4H-1 Phantom. Big and fast, crewed by a pilot and RIO to work the radar system, the Phantom was a dramatic step away from the smaller, single seat fighters of the previous decade as epitomized by the F8U Crusader. Today, it would set a record that still stands – 907.769 mph at an altitude of less than 125 ft.

orange streak that thundered by at 125 ft above the desert floor. The date is 28 August 1961 and a second attempt at the world’s low altitude speed record is underway. Flying a 3km closed course on the grounds of Holloman AFB, NM is the future of carrier-based interceptors: the YF4H-1 Phantom. Big and fast, crewed by a pilot and RIO to work the radar system, the Phantom was a dramatic step away from the smaller, single seat fighters of the previous decade as epitomized by the F8U Crusader. Today, it would set a record that still stands – 907.769 mph at an altitude of less than 125 ft.

The Phantom came to be as so many other designs out of the last decade – it started as an upgrade to a proven airframe that otherwise was suffering a shortfall in some area(s) of performance. In this case, it was the F3H Demon, which was suffering mightily from an underperforming power plant, the Westinghouse J-40. As detailed here (the first Flightdeck Friday), the J-40 was an extraordinarily disappointing engine – promising 11-14,400 lbs of thrust in its afterburning version, by many reports it barely produced 6800. In the meantime, the F3H was showing promise with the first integrated, all weather intercept radar system that used the new semi-active radar homing Sparrow AAMs. Even substitution of the Allison J-71 (producing the F3H-2N) fell short of what was considered safe to operate criteria for carrier ops.

In 1953, McDonnell Aircraft began work on revising the Demon, seeking to dramatically improve capabilities and performance. Several projects, including the F3H-E with a Wright J67 engine, the F3H-G with two Wright J65 engines, and the F3H-H with two General Electric J79 engines were forthcoming from this effort. Notably, the J79-powered version promised a top speed of Mach 1.97 (one of the criticisms of the current version of the F3H was its inability to break Mach). McDonnell brought this version forward to the Navy in September 1953, naming it the “Super Demon”. Setting it apart from the other purpose-designed aircraft of the day (read: single mission), it could be fitted with one- or two-seat noses for different missions, with different nose cones to accommodate radar, photo cameras, four 20 millimeter cannon, or 56 FFAR unguided rockets in addition to the 9 hard points under the wings and the fuselage. The Navy was sufficiently interested to order a full-scale mock-up of the F3H-G/H. However, with other fighter prototypes in the pipeline (Grumman XF11F (nee-XF9F-9) and Vought XF8U-1), the need for a supersonic fighter per se, had already been met.

McDonnell F3H-3G/H Super Demon FSE Mockup

McDonnell continued to re-work and refine the design, eventually converting it to an all-weather fighter-bomber with 11 external hard-points for weapons. On 18 October 1954, the company received a letter of intent for two YAH-1 prototypes, yet barely 7 months later, four Navy officers arrived at the McDonnell offices and, within an hour, presented the company with an entirely new set of requirements. Because the Navy already had the A-4 Skyhawk for ground attack and F-8 Crusader for dogfighting, the project now had to fulfill the need for an all-weather fleet defense interceptor. The addition of powerful radar capabilities necessitated a second crewman and the aircraft would be armed only with missiles.

Redesignated the XF4H-1 Phantom II (earlier names of Satan and Mithras were frowned upon by the government) in recognition of the all-weather intercept role, the Phantom carried four semi-recessed AAM-N-6 Sparrow III radar-guided missiles, using the AN/APQ-50 radar, and was powered by 2 x General Electric J79-GE-8 engines. Reflecting design lessons learned from the F-101 Voodoo, the engines sat low in the fuselage to maximize internal fuel capacity and ingested air through fixed geometry intakes. The thin-section wing had a leading edge sweep of 45 degrees and was equipped with a boundary layer control system for better low-speed handling. Wind tunnel testing revealed lateral instability requiring the addition of five degrees dihedral to the wings.In order to avoid a redesign of the titanium center section of the aircraft, McDonnell engineers angled up only the outer portions of the wings by 12 degrees which averaged to the required five degrees over the entire wingspan. The wings also received the distinctive “dogtooth” for improved control at high angles of attack. The all-moving tailplane was given 23 degrees of anhedral to improve control at high angles of attack and clear the engine exhaust. In addition, air intakes were equipped with movable ramps to regulate airflow to the engines at supersonic speeds. The XF4H-1 entered a flyoff competition with the Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III (subject of a future Flightdeck Friday), shortly after its first flight in May 1958.Although the Crusader III proved the more maneuverable fighter (foreshadowing future conflict in the skies over Vietnam), the XF4H won the day owing to having a dedicated radar operator and multi-mission capability. The Navy announced the winner on 17 December 1958 and the following year, carrier-suitability trials began with initial CARQUALs on the USS INDEPENDENCE (CV 62) in 1960 with the YF4H-1.

XF4H-1 Loaded Out in Air-to-Ground Configuration

for Competitve Flyoff (Boeing Photo)

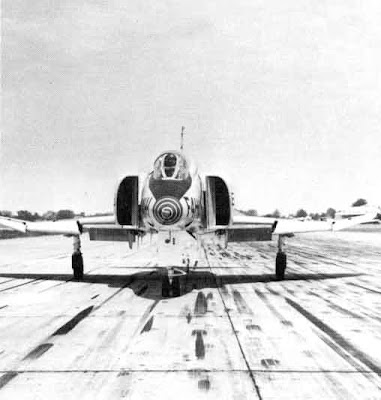

YF4H-1 Begins Carrier Trials on USS INDEPENDENCE (Boeing Photo)

During flight tests it was clear early on the Phantom had the potential to be a world-beater in terms of a series of records, many of which had recently been claimed by the Soviets. In light of the propaganda-fest the Soviets were harvesting over their rocket program, the time was right for a concerted effort at these records.

Two programs were established based on altitude – Operation Skyburner for the high altitude events and Operation Sageburner for the low altitude. Skyburn commenced on 9 Dec 1959 with an attempt at the world altitude record (Operation Top Flight). Taking off from Edwards AFB, the second YF4H-1, piloted by CDR Lawrence E. Flint, USN performed a zoom climb to a world record 98,557 feet (30,040 m). The previous record of 94,658 feet (28,852 m) was set by a Soviet Sukhoi T-43-1 (prototype of the Su-9 Fishpot). CDR Flint accelerated his aircraft to Mach 2.5 at 47,000 feet (14,330 m) and climbed to 90,000 feet at a 45 degree angle. He then shut down the engines and glided to the peak altitude. As the aircraft fell through 70,000 feet, Flint restarted the engines and resumed normal flight. To put this in perspective, the maximum altitude of the U-2A, then being secretly flown over the Soviet Union, was 75 – 80,000 ft. In 1960, records were set over closed courses of 500 km (311 mi) and 100 km (62 mi) respectively with speeds of 1,216.78 mph and 1,390.21 mph.

Sukhoi SU-9 FISHPOT

Continuing the run and celebrating Naval Aviation’s 50th anniversary, Operation LANA (a *very* tortured contraction – “L” for the Roman numeral for ’50’ and ANA for Anniversary of Naval Aviation) commenced with a coast-to-coast record run on 24 May 1961. Even with several tankings enroute, the crew of LT Richard Gordon (yes, the same Dick Gordon who would later go to the Moon in Apollo XII) and LT Bobbie Long completed the run in 2 hours and 47 minutes at an average speed of 869.74 mph, earning them the Bendix Trophy for 1961. Unfortunately, May 1961 saw the first Phantom fatality when CDR J. L. Felsman was killed when his YF4H-1 broke-up due to a pilot-induced oscillation while making the first attempt at a low-altitude speed record. The pitch control system was re-worked and simplified and on 28 Aug 1961, Operation Sageburner successfully saw a record of 902.769 mph set over a 3 mile course flying at or below 125 ft the entire time.

Operation LANA In-flight Refueling (Photo courtesy Skywarrior.org)

Operation LANA (Boeing Photo)

The Bendix Trophy

Skyburner also continued with a slightly modified Phantom (water injection was added to the engines) setting an absolute world speed record of 1,606.342 mph in December 1961, following a sustained altitude record of 66,443.8 ft. Time-to-climb records were set in 1962 using the newer F-4B and included 34.523 seconds to 3,000 meters (9,840 ft), 48.787 seconds to 6,000 meters (19,680 ft), 61.629 seconds to 9,000 meters (29,530 ft), 77.156 seconds to 12,000 meters (39,370 ft), 114.548 seconds to 15,000 meters (49,210 ft), 178.5 seconds to 20,000 meters (65,600 ft), 230.44 seconds to 25,000 meters (82,000 ft), and 371.43 seconds to 30,000 meters (98,400 ft). Although not officially recognized, the Phantom zoom-climbed to over 100,000 feet (30,480 m) during the last attempt. The remarkable series of record attempts was brought to an end with this series. With the exception of the Skyburner absolute speed attempt, all of these records were set by unmodified production aircraft flying without external stores. Subsequent aircraft that claimed the speed and altitude records (MiG-25 and F-15 Streak Eagle) were modified and stripped to bare weight.

The YF4H-1 that set the low altitude speed record is in “display†storage at the Smithsonian’s Garber facility wearing its Sageburner colors and awaits restoration for eventual display either at the NASM or NASM annex at the Udvar-Haazy Dulles Annex.

Sources:

http://www.nasm.si.edu/research/aero/aircraft/mcdonnel_F4A_sage.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F-4_Phantom_II

http://www.faqs.org/docs/air/avf4_1.html#m2

http://wapedia.mobi/en/F-4_Phantom_II?p=1

Don’t forget to stop by the Daily Brief for today’s posting on Fightdeck Friday —

the Fabulous FORD (F4D)…

Very nice work on the Phantom missions. Doing the same from here. Please advise re the source of the F-4 Pictures.

I had heard (a loooong time ago) that the Russians were doing that zoom climb and shoot from the top of the arc thing at the U2 Gary Powers was flying… and the missiles were falling short. Which means my grand children may someday actually find out how high the U2 actually can fly. That is not to denigrate in any manner the performance of the F4, a fabulous jet from any standpoint; and my understanding still one of the fastest jets ever in the U.S. arsenal. It is almost sad to see functional F4s being used as target drones…

So whenever I see one of those published ceilings for the U2, or how some jet (other than the SR71) flew higher than the U2, I kind of snicker, take it with the salt shaker, and read on.