Flightdeck Friday: Valour-IT Challenge Edition – The B-58 Hustler

At the start of the ’07 Valour-IT Challenge fundraiser, we exhanged an offline challenge (and yes, a few snarks too…) with Mike over at team Air Force, the gist of which was whomever showed up Rocket Last (aka Tail-end Charlie) would host an article on the plane of the other team’s choosing – here as oneof the Flightdeck Friday posts – there, as a Saturday Tarmac post. Since today’s feature is prominently lacking a "USN" on its fuselage, we will leave it to you, good reader, to determine which team finished ahead of the other… So for Mike, Buck and the rest of the folks at Team Air Force, congrats and this Flightdeck Friday’s for you. – SJS

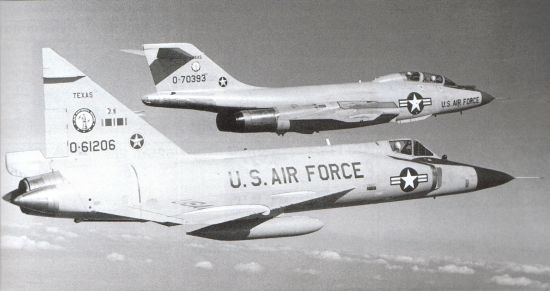

December 1, 1959. A gleaming silver arrowhead touches down at Carswell AFB, Texas and in so doing ushers in a new, albeit brief, era for the Strategic Air Command. The centerpiece of that era was the B-58 Hustler which sought to bring long-range, supersonic strike capabilities to SAC’s inventory. However, events on the other side of the continent and world were already in motion that would bring this era to an early end. In the interim though, nothing else in the operational inventory anywhere else in the world, save a super-secret reconnaissance aircraft, would hold crews in awe of its record-breaking capabilities in an operational aircraft – and a bomber at that.

By the end of the first full decade of jet flight, there was one mnemonic that drove fighter and bomber development – “speed is life” Everywhere one looked the effort to build in more speed, to go faster and fly higher was in full gear. Fighters, epitomized by the F-104 grew long, slender and needle nosed in their effort to minimize drag. Missiles were carried in internal bays that opened only when it was necessary to launch them. Even guns themselves were absent from the new designs being fielded like the F-106 and the Navy’s new F4H. The concept of a turning dogfight that culminated in a close in guns kill was rapidly being relegated to the same shelf that held the leather helmet and white scarf – modern combat would be fought long-range where the enemy was but a faint trace on a radarscope or delicate sketch of vapor on a midnight blue sky. Missiles, likely with nuclear warheads, were the weapon of choice because the target was rapidly streaking toward the defended area bearing its load of nuclear destruction.

On the bomber’s side it was the same move/counter-move that first began in the skies over Europe four decades previous. Bombers ever seeking higher sanctuary – above ground-based artillery (“flak”), above the highest flying fighter; into the thin upper atmosphere where engines were starved for air and the nimblest of fighters stumbled and mushed about like drunken mules. At the same time their payload had grown substantially deadlier – from the thousand pounders of the last war to thermonuclear weapons that, like the Mk 53, ranged in the megatons for a single bomb yield.

Those were the imperatives that, in 1949, drove Convair’s (later to become part of General Dynamics) design submission to the Generalized Bomber Study (GEBO II) issued by the Air Force’s Air Research and Development Command. The Air Force already had several designs in production or development – the B-29 and B-50 were operational along with the new B-36 and the first jet designs, Boeing’s B-47 and B-52 were in the process of moving from the design boards to reality. Thing was, they were all subsonic. The sound barrier had already been broken and over on the fighter side, it was expected that speeds would continue to climb, reaching and surpassing the supersonic threshold in the near future. To be survivable, bombers would have to fly higher and faster.

In April 1950, the GEBO II requirements were revised to specify a system with a range of up to 4500 nautical miles with cruising speeds in the .9 to 1.5 mach range. Convair, which coincidently had been working on fighter development, proposed a small delta wing “parasite” solution in January 1950. Carrying a two man crew, the parasite bomber was actually a composite consisting of two parts – a manned, single-engine delta winged aircraft that employed two additional (and jettisonable) wing-mounted engines, and a weapons pod that was winged and had a single engine for powered flight the final 100 nm to the target by itself. A B-36 (also a Convair product) would serve as the mother ship, launching and recovering the parasite bomber. All told, the parasite would tip the scales at 100K lbs and cruise to the target at 1.3 mach with a 1.6 mach dash capability in the vicinity of the target. Final cruising altitude would be 48,500 ft where the weapons pod would be released.

Over the course of the next several months the concept would undergo revision, eventually adopting a somewhat more conventional CONOPS (no longer a parasite) but retaining the idea of a detachable/jettisonable weapons pod that would also hold fuel. The final design, MX-1964, was eventually chosen as the winner of the Supersonic Aircraft Bomber (SAB-51) and Supersonic Aircraft Reconnaissance (SAR-51) proposals which were drawn from the successor to GEOB II, the General Operational Requirement (GOR) worldwide for supersonic bombers. In doing so, Convair beat out rival Boeing’s MX-1965 design.

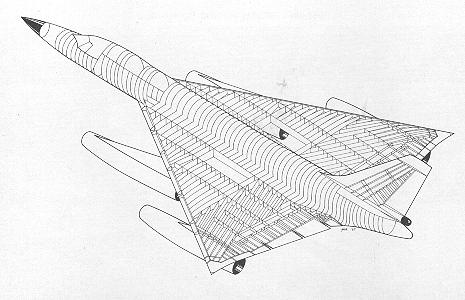

With a contract awarded in February 1952, the XB-58 would undergo further and final design refinement, emerging as a delta-wing aircraft with a leading edge swept to 60 degrees (training edge was 10 degrees) and fitted with four, independently podded Pratt & Whitney J79 afterburning engines (initial prototypes were planned t be outfitted with the J57 until the J79 became available, but as it turned out, the J79 was available by the time the prototype required engines). Area-rule, learned from Convair’s experience with the XF-102, was also added. Self-protection (beyond just speed) was added in the form of a new GE-T-171 (later M61) 20mm Vulcan rotary cannon mounted in the tail. First flight was scheduled for early (later mid-) 1956.

Testing & Controversy

As compelling as the aircraft appeared to be on paper, it had its detractors in high places, including the head of SAC, the venerable General Curtis LeMay. In a January 1955 memo, he criticized the purchase of the B-58 given its range was half that of the B-52, that subsonic bombers could accomplish the conventional bombing mission much more effectively and that strategic nuclear strike role would be eventually taken on by ICBMs. Nevertheless, the advocates still won with the Air force ordering several YB-58 trial models (11) that December.

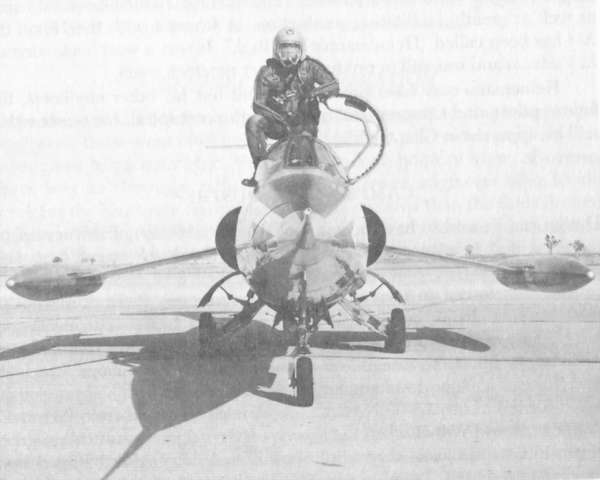

Other controversies swirled around the Hustler, as it came to be called (originated by the Convair engineering crew and officially adopted by the Air Force). The B-58 was an extraordinarily advanced aircraft for its time, using an all-hydraulic flight control system, advanced navigation and weapons system computers and sensors and new materials to endure the high heat associated with prolonged travel at mach-speeds. Internally, the aircraft was segmented and framed not unlike a naval vessel with transverse duralumin spars that were corrugated for strength. Almost every available void in the wings and fuselage served to hold fuel to feed the J79’s prodigious appetite at speed. Towards the rear of the fuselage this included a trim or balance tank which helped keep the aircraft from pitching nose down in supersonic flight as the center of pressure shifted aft of its location for subsonic flight. Externally, extensive use of laminate panels provided strength without the weight penalty usually associated with traditional construction. In some areas, that laminate consisted of fiberglass or aluminum panels surfaced on either side with thin aluminum facings. In areas exposed to high heat, a honeycombed material based on stainless steel was used. All panels were held in place with titanium screws. As a result, the Hustler tipped the scales at a mere 55,560 lbs (empty).

The trade-off in weight saving was offset however in cost. Manufacturing and fitting panels to extraordinary tolerances proved to be extremely costly. Additionally, because of the tight tolerances required, any panel replacement required the aircraft to be mounted in a high-precision (and extremely expensive) jig – even for operationally deployed aircraft undergoing squadron-level maintenance.

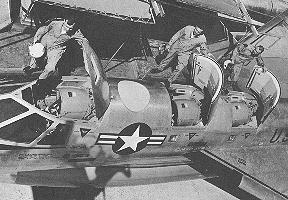

The complexity of the aircraft demanded three aircrew – a pilot, bombardier-navigator and defense systems operator. All sat in tandem, isolated in their small cabins, strapped into their ejection seats for flights that could last upwards of eight-plus hours. Although initially conventional in nature, the ejection seats were modified after several crew deaths in 1962 to a clamshell capsule to protect the crew from flail injuries during high-speed ejections.

Built around the Sperry-Rand AN/ASQ-42V, the B-58 weapons system gave strong hints at just how complex this next generation of warplane promised to be. Behind the B/N, the DSO had an extremely capable ECM suite available that included the AN/ALQ-16 active jammer, and AN/ALE-16 chaff dispenser. As originally configured, the 36,000 lb (fully loaded) MB-1C weapons pod would carry both fuel and a W39Y1-1 nuclear warhead. Weighing in at around 6,400 lbs, the W39 had a yield of 3.8MT. Later, as the B-58 entered operational service, four more external hardpoints were added to carry the B43 and B61 nuclear weapons.

After running through a flight and operational test program that saw more than its fair share of teething problems, the first operational B-58 was ready in early 1959. At the time, the Air Force had planned on a total buy of 290 B-58s, produced at the rate of 6/month, which in turn would outfit 5 wings. However, in July, SAC was informed that there were budget shortfalls and was forced to scale back to 148 a/c. The program was scaled back further, but even then, by the end of 1961 cost of the program (now 118 a/c) was over $3B through FY61.

Problems continued with the weapons and ECM systems and the J79’s were having problems of their own, including an unnerving tendency to cause intermittent yaw at supersonic speeds. Along the way seven aircraft were lost between December 1958 and September 1960 including one that broke up in flight. Convair test pilot Raymond Fitzgerald and Convair flight engineer Donald A. Siedhof were both killed. The flight was attempting to collect data on induced side loads when experiencing engine high speed. Although the cause of the accident was never adequately explained, it appears that a design flaw in the aircraft’s flight control system and defects in the integrity of the vertical fin structure were to blame. Similarly, the next generation of fighters also experiencing some losses due to failures in the flight control arena – most notably the YF4H which suffered its first fatality in May 1961 with an in-flight break-up following a pilot induced oscillation.

Operations and Early Exit

The first operational wing was the 43rd, brought over to Carswell AFB from Davis-Monthan AFB. Because of the cutbacks, the originally envisioned 45-plaqne wings were scaled back to 36 vice 45 aircraft. Delayed from being declared operational by the Air Force, the 43rd was finally declared combat ready and assumed alert duties in August 1962. Eventually the 305th would join the 43rd Bomb Wing and with per unit prices approaching the record sum (for 1962) of $14M, further procurement of the Hustler was terminated. Never a popular a/c with Defense Secretary McNamara, he ordered an early close out to the program in 1965 and in 1970, the last Hustler left for storage at Davis-Monthan.

Along the way, the Hustler set several world records and earned some pretty substantial hardware, to include the McCay, Thompson and Bleriot trophies. Specific events included:

-

Quick Step I in which 59-2442 of the 43rd BW set three new speed-with-payload records (0, 1000 and 2000 kilogram payloads) by flying at a speed of 1061 mph over a closed circuit 2000-kilometer course on January 12, 1961. On the same flight, the crew also set a 1000-kilometer record by flying at an average speed of 1200.19 mph. The closed circuit and 2000-kg records still stand.

-

On January 14, 59-2441 set three international speed-with payloads by flying at a speed of 1284.73 mph over a 1000-km closed circuit. The crew of 59-2441 (Lt. Col. Harold Confer, Lt. Col. Richard Weir, and Major Howard Bialas) were awarded the 1961 Thompson Trophy for this feat.

-

On May 10, 1961, 59-2451 crewed by Major Elmer Murphy, Major Eugene Moses and Lt. David Dickerson, flew a 1073-kilometer closed course at an average speed of 1302.07 mph, taking 30 minutes and 43 seconds to complete the course. This won the Bleriot Trophy, which had been established back in 1930 by the famous French aviator M. Louis Bleriot to be awarded permanently to any aircraft flying for at least a half-hour at an average speed of 2000 km/hr (1242.74 mph).

-

On May 26, 1961, 59-2451, crewed by Maj. William Payne, Capt. William Polhemus, and Capt. Raymond Wagener, while enroute to the 1961 Paris Air Show, set a New York-to-Paris speed record, covering the 3626.46 mile route in 3 hours 19 minutes 58 seconds (an average speed of 1089.36 mph. The flight also set a Washington DC to Paris (3833.4 miles) speed record of 3 hours 39 minutes 48 seconds (average speed of 1048.68 mph). The crew was later awarded the prestigious Mackay and Harmon Trophies for this flight. Sadly, the return flight crew, consisting of Maj. Elmer Murphy, Major Eugene Moses, and Lt. David Dickerson (the same crew who had won the Bleriot Trophy two weeks earlier) were killed when 59-2451 crashed on June 3 following departure from Le Bourget Field.

-

Further records were set on March 5, 1962, when 59-2458 crewed by Capt. Robert Sowers, Capt. Robert Macdonald, and Capt John Walton set a transcontinental speed record by flying nonstop from Los Angeles to New York and back again. The first leg (Los Angeles to New York) was completed in 2 hours 0 minutes 56.8 seconds at an average speed of 1214.71 mph. The return leg was completed in 2 hours 15 minutes 48.6 seconds, at an average speed of 1081.77 mph. This return flight was particularly notable, because it was the first transcontinental flight in history that moved across the country at a speed faster than the rotational speed of the earth. (source: http://home.att.net/~jbaugher2/b58_4.html)

Special Versions and Oddities

Recce: Besides the expected trainer versions of the B-58, there were a number of special versions and concepts that sought to take advantage of the B-58’s capabilties. One of the more practical (or so it was thought) configurations was as a reconnaissance aircraft. It was becoming clear before 1961 that the days of unmolested U-2 overflights were drawing to a close and something faster would have to be developed (It was – the Oxcart program was the follow-on and gave birth to first the A-11 and ten the A-12/SR-71. – SJS). The B-58’s weapons pod was modified to carry the AN/APQ-69 side-looking radar. The APQ-69 was a side-looking radar, used for collecting imagery intelligence (IMINT). Using radar in combination with traditional film cameras enabled a full spectrum to be covered and in some cases with the radar, reveal targets otherwise obscured by natural or man-made impediments. The problem was the APQ-69 had a huge antenna – over fifty feet in length (the largest antenna carried aloft in an aircraft at the time) and took up virtually all of the available space int he B-58’s weapons pod. Test flown several times, it succesfully managed 10 ft resolution out to 50 nm from the B-58. Unfortunately because of the configuration, the B-58 had to fly subsonically and the added drag of the blunt nosed module served to decrease the Hustler’s already shortened legs even more. Eventually that project was put on hold and the equipment put up in storage. All was not lost though as another atempt at turning the Hustler into a recce bird – this time throught he Quick Check program and Goodyear’s X-band AN/APS-73 synthetic aperature radar. With a smaller profile (the antenna was mounted in the nose) the APS-73 had a claimed resolution of 50 ft @ 80 nm – but like the APQ-69, the Hustler still had to be at subsonic speeds. Unlike the APQ-69, the ALR-73 was used in a limited operational capability, including at least one overflight of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. There were no further attempts at a recce version of the Hustler after the ALR-73 was removed frmo the testbed aircraft and mothballed.

Missile Plaform: In 1959 the Air Force was very much interested in exploring the use of manned bombers as platforms to launch ballistic missiles. Contracts were let with Martin (WS-199B Bold Orion using the B-47) and Lockheed (WS-199C High Virgo used with the B-58) as proof of concepts for an ALBM (Air-Launched Ballistic Missile). Lockhed developed the High Virgo using components from the XQ-5 Kingfisher, X-17, Polaris SLBM and Sergeant MRBM missiles, many of which were already tried and tested. CONOPS was for the B-58 to be in supersonic flight at high altitude and drop the missile whose motor would ignite a few seconds after seperation. The first test, 5 Sept 1958, was unsuccessful when the missile’s control system faild a few seconds after launch. The second test, 19 Dec 1958, was successful with the missile reaching an altittude of 250,000 ft and covering a distance of 185 nm at Mach 6. The third flight wa also succesful and utilized an inertial navigation system for the first time. The fourth and final flight involved an attempt to photograph the Explorer V satellite with the B-58 flying at a max speed of Mach 2. Seperation and ignition were successful, but 30 seconds into the flight all contact wa lost and it was unable to be determined if the attempted encounter was successful or not. ( A similar attempt, this time as a potential ASAT, was conducted by the Bold Orion vehicle off a B-47. That attempt was successful with the missile passing within 4 miles of the Explorer VI satellite, at that time at an altitude of 156 nm. The Soviets took notice and not long afterwards began their ASAT program… – SJS) The result of both the Bold Orion and High Virgo programs was development on the GAM-87/AGM-48 Skybolt, designed to be launched off the B-52 and Britain’s Vulcan bombers.

Conclusion

The B-58 represented the last of the special-bred bombers (at least until the advent of the so-called “stealth” bombers), eventually being supplanted by the FB-111 variant of the F-111 and by the B-52 which cost only a third of the B-58 to operate and was able to be used in a wider range of missions. The arrival of surface to air missiles and integrated air defense systems removed the sanctuary provided by high altitude/high speed penetration – now, to ensure survivability, aircraft had to fly low, nape of the earth profiles to minimize exposure to hostile radars. The B-52 and FB-111 could do that, the B-58, not so.

Beset by technical problems in the development process, burdened by high procurement and operational costs and limited in operational capability, the B-58 nevertheless was one of those signatory aircraft that captured the imagination and for one brief moment, ruled the roost as the fastest, highest flying bomber in the US inventory.

Specifications (B-58A)

Resources:

- http://home.att.net/~jbaugher2/b58.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B-58_Hustler

- http://www.b58hustler.net/

- http://www.b-58hustler.com/

- Convair B-58 Hustler (Paperback) by Bill Holder

- http://designation-systems.net/dusrm/app4/ws-199.html

Data from Quest for Performance

General characteristics

- Crew: 3: pilot; observer (navigator, radar operator, bombardier); defense system operator (DSO; electronic countermeasures operator and pilot assistant).

- Length: 96 ft 9 in (29.5 m)

- Wingspan: 56 ft 9 in (17.3 m)

- Height: 29 ft 11 in (8.9 m)

- Wing area: 1,542 ft² (143.3 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 0003.46-64.069 root, NACA 0004.08-63 tip

- Empty weight: 55,560 lb (25,200 kg)

- Loaded weight: 67,871 lb (30,786 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 176,890 lb (80,240 kg)

- Powerplant: 4× General Electric J79-GE-5A turbojets, 15,600 lbf (69.3 kN) each

- * Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0068

- Drag area: 10.49 ft² (0.97 m²)

- Aspect ratio: 2.09

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.1 (1,400 mph, 2,240 km/h) at 40,000 ft (12,000 m)

- Cruise speed: 610 mph (530 knots, 985 km/h)

- Combat radius: 1,740 mi (1,510 nm, 3,220 km)

- Ferry range: 4,720 mi (4,100 nm, 7,590 km)

- Service ceiling: 63,400 ft (19,300 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,700 ft/min (13.7 m/s)

- Wing loading: 44.01 lb/ft² (214.9 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.919

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 11.3 (without weapons/fuel pod)

Armament

- Guns: 1× 20 mm (0.787 in) T171 cannon

- Bombs: 4× B-43 or B61 nuclear bombs; maximum weapons load was 19,450 lb (8,823 kg)

SJS

I loved this plane growing up.

I had the chance to talk to one of the

docents at the USAF Museum who flew

one-he loved the plane as well

and told me a few colorful stories.

I know it had to hurt a little to do a story

on a USAF plane-Thanks for doing this.

Blue skies,

Rich

I’ve always liked the B-58. My cousin worked for Bendix (waay back when!) as a draftsman, and he was proud of his contribution to the cockpit design. This started my desire to be in aviation.

Still, despite respecting the AF and enjoying the visits to AF bases, I still prefer Naval Aviation. On Tin Cans. Best of both worlds.

Well done! Great “Flight Deck” episode, SJ!

A good sport you are SJS. 😛

And thanks for the ‘glass cockpit” lesson.

I second Michelle, sir. This was an excellent post and you have my thanks.

Living/growing up in SAC HQ’s shadow I had my own close encounters with the Hustler while growing up. Neat airplane that stretched the envelope a little to much for its day – like so many other jets born in the 50’s.

– SJS

Dang, SJS… a real tour de force!! I thoroughly enjoyed this, to say the very least. And the images you selected to accompany the narrative are simply outstanding. Thank you!

Tangent: My father worked for Nortronics (and other Northrop divisions) after he retired from the AF back in the 60s and 70s… and was associated with the Skybolt program. Christmas of 1962 (after Skybolt was canceled) was pretty bleak in our house, to say the least. But…he landed well and was off on another program in January of ’63. A lot of his friends and associates didn’t fare as well and were laid off. It was a sad time. (And I remember it well; I was a senior in high school then.)

Buck:

Re. the Skybolt cancellation; that left the Brits in a big time lurch as they had planned to use it as the centerpiece of their nuclear deterrent and felt the US pulled the rug out from underneath them. As a result, the US agreed to sharing the Polaris SLBM program and the rest, as the saying goes, was history…

– SJS

Very nice SJS. The pictures especially are amazing. Sad to say the Hustler out at the SAC Museum (I refuse to call it by its new name) hasn’t been restored yet. It still looks quite nice, even in its slightly beat up state. Have to say I’m a bit jealous of the whole growing up in SAC HQ’s shadow thing…Offutt isn’t nearly as much fun anymore.

Oh, the recip will be up at my place sometime this week…we’re still recovering a bit from the weekend’s festivities…

Mike:

I’ll bet… BTW, happy 21st and remember the old saw about the hair of the dog that bit you being a cure…. 😆

BTW, happy 21st and remember the old saw about the hair of the dog that bit you being a cure…. 😆

– SJS

My favorite!

(F-4 Phantom doesnt count because she was NAVY)

🙂

Hi I just read this article and was glad to find it. I worked for General Dynamics and assigned to the B-58 Mod/Iran program which was the last update as far as I know to the aircraft. As the program drew to a close the final aircraft were sent to the bone yard and would never fly again. I was privladged to work with Col James K. Johnson during that program who was wing comander of the B-58’s when they went to the Paris Airshow. He was drumed out of the Airforce shortly after the 2nd crash in Paris as acording to his own words they needed a scape goat.

I was fortunate to have had the opportunity to work on the B58 as a Bomb/Nav technician at Little rock AFB 1967-1969. If it were still flying today, it would still be ahead of most aircraft flying today!

As a young lieutenant in 1967 I had control of SAGE air defence radars across Washington, Montana, the Dakotas, and Canada during an exercise called “Snowtime.” I was in charge of ECCM at the Great Falls SAGE Direction Center.

We thought we were in pretty good shape because of the frequency diversity in radars we enjoyed. Sitting near the base I had an FPS-24 operating at 200MHZ and there was an FPS-35 a little north operating at 300 MHz. We knew from previous experience with the B-52s at Minot and Grand Forks that they didn’t have the jamming gear to touch those radars. So, we had them peaked and tweaked and were accepting all the data they could process down two phone lines. (1200 baud x 2 if memory serves)

We watched the Buffs take off out of Minot and head north before they turned around. Even down low, we picked them up pretty well because of the high terrain and, frankly, really good radars! They were about to reach the CAP line when poof, everything went white.

We jumped radar frequencies, fiddled with receivers and antennas, and did all the things that you do, but we were having a hard time. At the debriefing, the word came out. Two B-58s, one low and one high, had taken us down across three states. Poof. Better jammers and antennas than the buffs.

An interesting lesson in the power of that bird.

I WAS CREW CHIEF ON 0053 IN THE LATE 60S AT GRISSOM

THOSE WHERE GOOD TIMES

THANKS FOR THE MEMORIES SSGT M JOHNSON

My dad Lt Col Andrew G Martin flew one of the last B-58’s to the graveyard and he also had the most flight hours in the B-58 we were with the squadrons at Carswell, Little Rock and Grissom.

Enjoyed the article. Grew up in s. okla. watching b36 b58 test flights out of cars well. Was watching the 58 that broke up over Duncan,Ok. Watched the smoking pieces spiri

Wasn’t finished. Watched the smoking pieces spiral down. The plane was so high prior to the accident it looked like a tiny triangle. Later went to work at GD. The B58iran program was still at ft worth. Used to drive from Springtown to cars well just to watch them take off. Exciting plane.